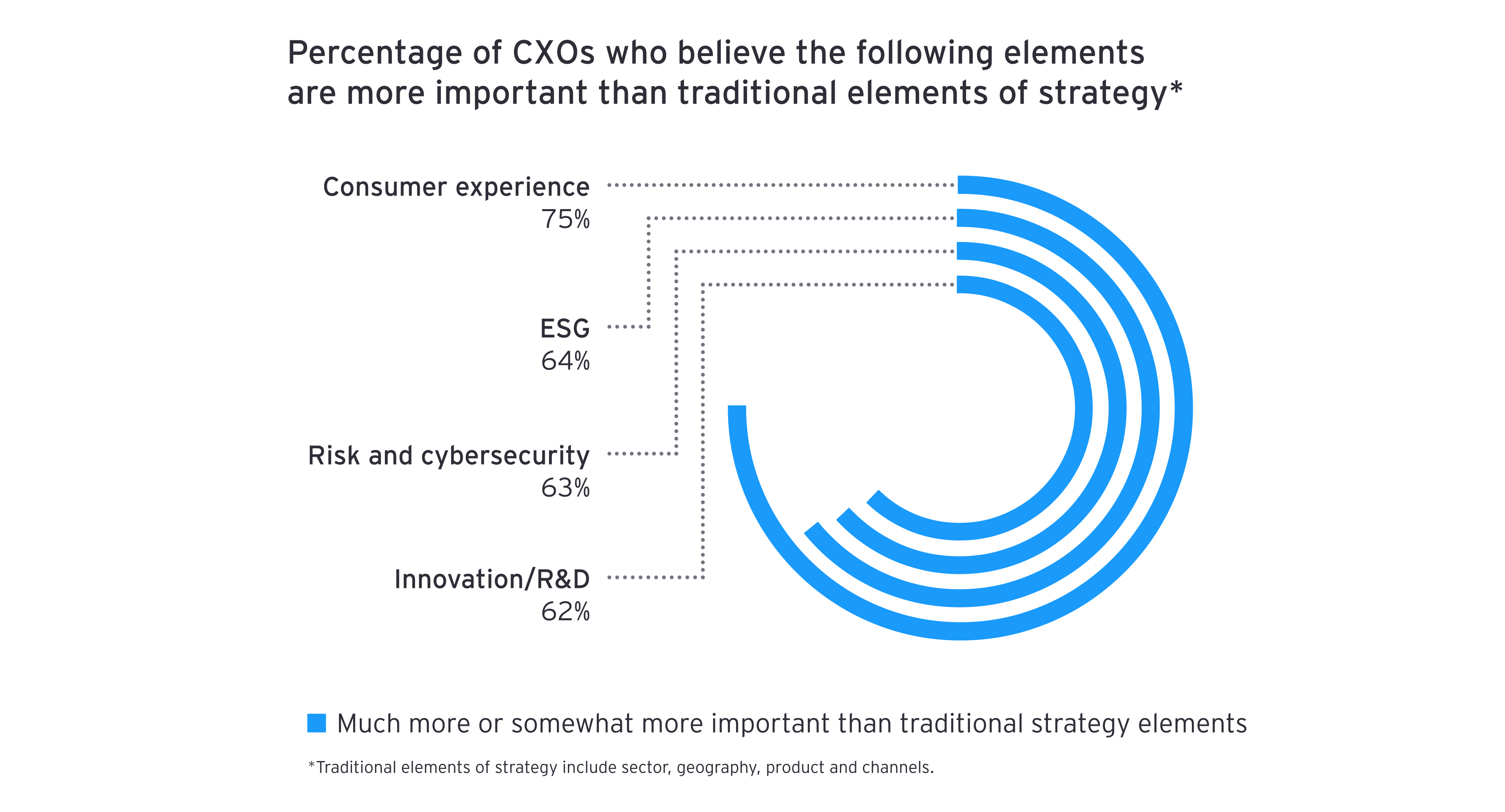

A first step for any CSO is to define which elements will be critical and a competitive differentiator going forward. Consumer experience is on top of the list (75% of executives say it’s more important than traditional elements of strategy), and across many organizations, the strategy function has had a substantial role already in developing a distinctive consumer experience. New elements that rank high but historically have not been in the mandate of corporate strategy include data strategy, innovation strategy, digital strategy and human capital strategy, among others.

For each element that matters going forward, a second step that the CSO can take is to conduct a thorough benchmark study of the company position in relation to current or new competitors. If in the past corporate strategy had a clear view on the product portfolio compared with competitors’, now it needs to supplement that with a clear view on the digital capability, or other core capability, vs. competitors’ as well.

Do you have a clear, fact-based benchmark of your digital capabilities? Is your data and analytics strength superior to competitors? How strong is your innovation pipeline vs. the market?

These are questions that CSOs need to help answer in an objective and strategic manner. The mapping, benchmarking, competitive analysis and evaluation of relative strength is something the corporate strategy function must own, regardless of whether it is evaluating products, markets and channels or evaluating digital, data, human capital and other elements that are critical going forward.

Developing new capabilities

Another key step where corporate strategy has a vital role is in building a portfolio of initiatives to develop new capabilities. Investments in these capabilities need to be treated with the same rigor, metrics and accountabilities as any other strategic investments. What is the expected return on the digital investments? What are the specific business impacts on data and analytics capabilities? Where is the highest impact and usage of innovation across the portfolio? These are additional questions that CSOs need to help answer in an objective manner, maintaining a strong discipline in measuring and tracking the results from these investments in capabilities.

Corporate strategy can use a governance structure to drive co-accountability between each relevant function (e.g., chief digital officer, head of analytics, chief innovation officer) and the rest of the organization that extracts value from those functions. For example, in our work with clients, when we see a digital program being boxed as an “IT project” without the connecting elements to the business and the rest of the organization, we typically see those programs fail to deliver strong commercial benefit. Establishing the appropriate governance (e.g., digital strategy steering committee), confirming the dots are connected across departments and linking back each of these elements to the fundamental corporate strategy of the company are key actions where CSOs can drive value.

.

3. Accelerating to strengthen emerging capabilities

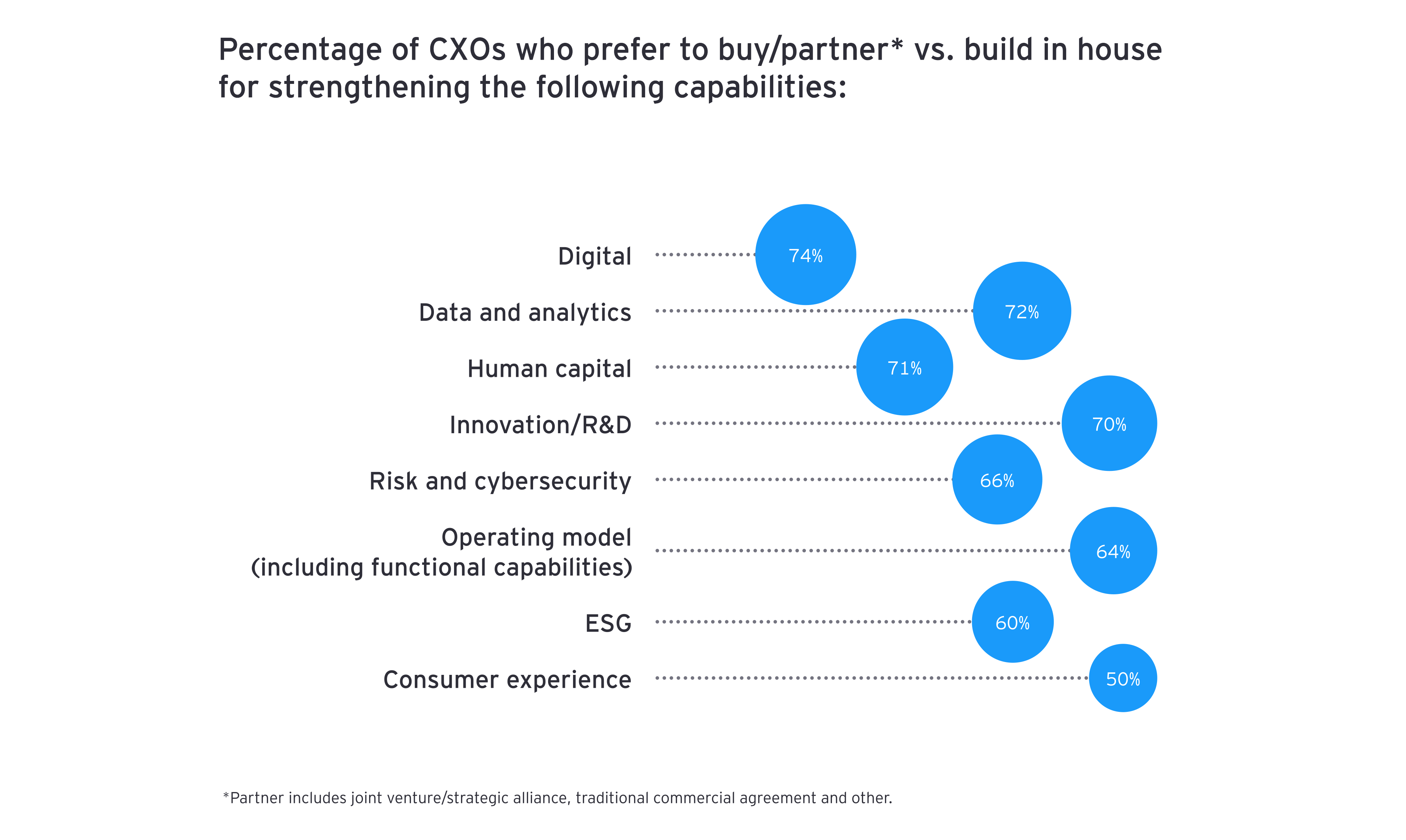

Companies need to strengthen their capabilities quickly, particularly in digital, data and analytics, and innovation, as well as add people with skills to support these capabilities. However, these capabilities can be difficult to build organically, both from a talent and cost perspective. In fact, in our survey, C-suite executives prefer to buy or partner, rather than build organically, for most of these capabilities, particularly digital, data, talent and innovation (see Figure 3).