Higher education institutions have continued to increase the amount of long-term debt they hold during a period when enrollment growth in the sector has slowed and is expected to decline. This raises a question about whether the sector is approaching a limit to the benefits of debt-financing. EY-Parthenon’s joint study with NACUBO found that decisions about debt are often made primarily on the basis of financial metrics that indicate if an institution can take on further debt without sufficient attention paid to whether it should.

Future debt levels are uncertain

The increase in long-term debt over time exceeds the growth of FTE enrollment at public and private not-for-profit four-year institutions, which has been below 1% per year from 2011 to 2019, according to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). As a result, the debt burden per full-time student has increased substantially for many institutions and, as of 2019, was $24.3k overall. This varies significantly by institution type, with large privates having the greatest debt burden per FTE at $54.8k and small publics having the least at $13.3k.

While most institutions said their debt issuance during the COVID-19 pandemic was in line with expectations, it remains to be seen how the overall sector and attitudes toward debt may change over a longer term. Fifteen percent of CBOs expressed uncertainty about future debt levels for higher education, and 55% indicated an expectation that debt levels will continue to rise over the next five years. Sector leaders have emphasized the importance of focusing the post-COVID period on transformational change rather than a return to business as usual. For example, online learning is becoming a more viable choice for students seeking flexibility and affordability, which may disrupt higher education’s traditional residential model for a meaningful share of institutions. Sector leaders also acknowledge the difficulties of focusing on transformational change when students, families, faculty and staff are looking for some return to stability.

How debt capacity is assessed

Whether institutions pursue a path of transformation or recommit to pre-pandemic priorities, the decision of how to finance strategic projects is an important one that will have implications for years to come, given that the debt maturities issued by higher education institutions are typically 30 years or longer, according to interviews with CBOs.

Debt is the largest single source making up budgets for capital projects, at 42% across all institutions, according to the June 2021 NACUBO EY-P Institutional Debt Survey. About 71% of institutions have a formal policy or codified set of practices that are used to guide decisions about when debt is issued and for what purpose, and another 12% are in the process of developing these. Policies typically include:

- Guidelines on capital projects eligible for debt financing

- Limits on the length of a long-term debt issuance

- Methodology on how to assess debt capacity

- A set of financial ratios/metrics that can act as constraints on total debt levels

- Requirement of a payment plan for debt service expense over the entire lifetime of the issuance

- Specification of specific stakeholder approvals needed

In fact, debt burden ratio and viability ratio emerged as the most frequently relied-upon metrics to assess levels of long-term debt.

Institutions use these thresholds to assess the current state and project the impact of a future debt issuance. If forecasting suggests that a planned debt issuance would push the institution above its set threshold, it may delay the project until additional fundraising or cash reserves can be applied to reduce the overall debt burden required or until the debt can be restructured to achieve more favorable terms. Therefore, one of the primary ways that institutions assess their level of debt is in relation to how much they can take on according to externally validated measures and lender terms. This provides an incomplete picture, unless institutions also evaluate whether a particular debt-financed project is something they should take on.

How value is determined

The two most frequent ways that institutions define the value of capital investment have both merits and limits:

Indirect assessments attempt to quantify the financial impact of a project funded by debt with a series of often qualitative assumptions. For example, a project may be expected to drive differentiation, which drives student interest and applications, which, in turn, may drive selectivity and, ultimately, net revenue per student. This can have a positive financial impact on the institution overall. But the logic may not fully factor in sector trends or effectively evaluate the level and impact of differentiation achieved.

Direct assessments of cash flows can be performed when there is auxiliary revenue generated from an investment, such as the impact of a new dorm building that is expected to boost enrollment of residential students or boost room and board fees. However, this type of assessment may lead to too narrow a view of how the project affects the overall business model, by attributing benefits to the project only, and therefore create a more favorable view of project economics than exists in practice.

Overall, strategic value can be measured in many ways because institutions have missions beyond financial viability. However, since a viable financial model is required so that the institution can continue operating and fulfilling its mission, we posit that revenue growth (as distinct from pure enrollment growth) can be used as a proxy to measure successful capital investments.

Looking at revenue growth over the past five years, there is a broad distribution of outcomes, suggesting that not all institutions are equally able to generate value from the debt-financed investments that they are making.

How can future decisions be made?

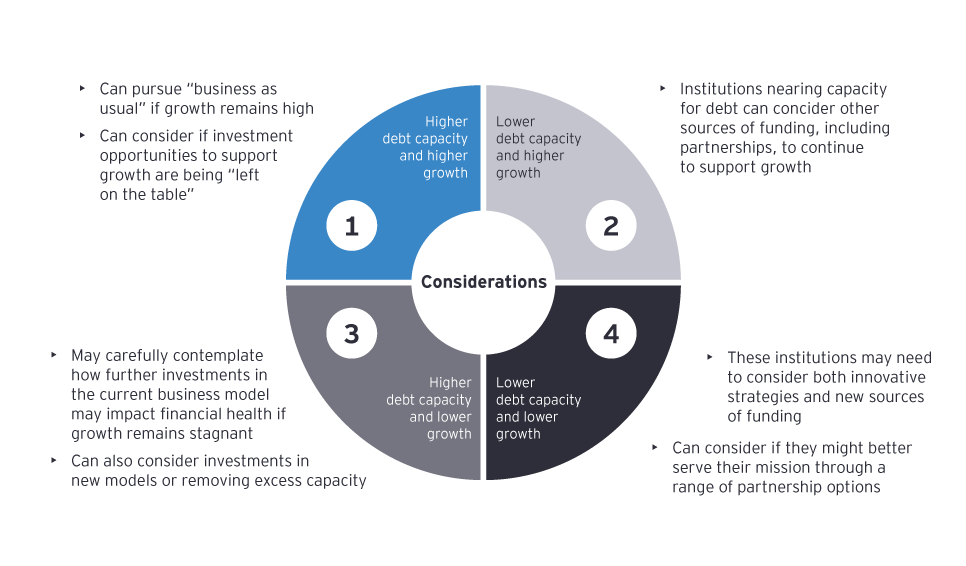

Institutions can be divided into four different categories (illustrated in Figure 1), based on their level of debt capacity and their demonstrated ability to realize capital investment value. Each category can incorporate a set of considerations into their decision making.