As manufacturers grapple with how to respond to the impact COVID-19 is having on their businesses, the critical importance of manufacturing operations’ resilience has never been clearer. But even before the current crisis, manufacturers recognized the need to strengthen their ability to mobilize and bounce back from disruptions to the business.

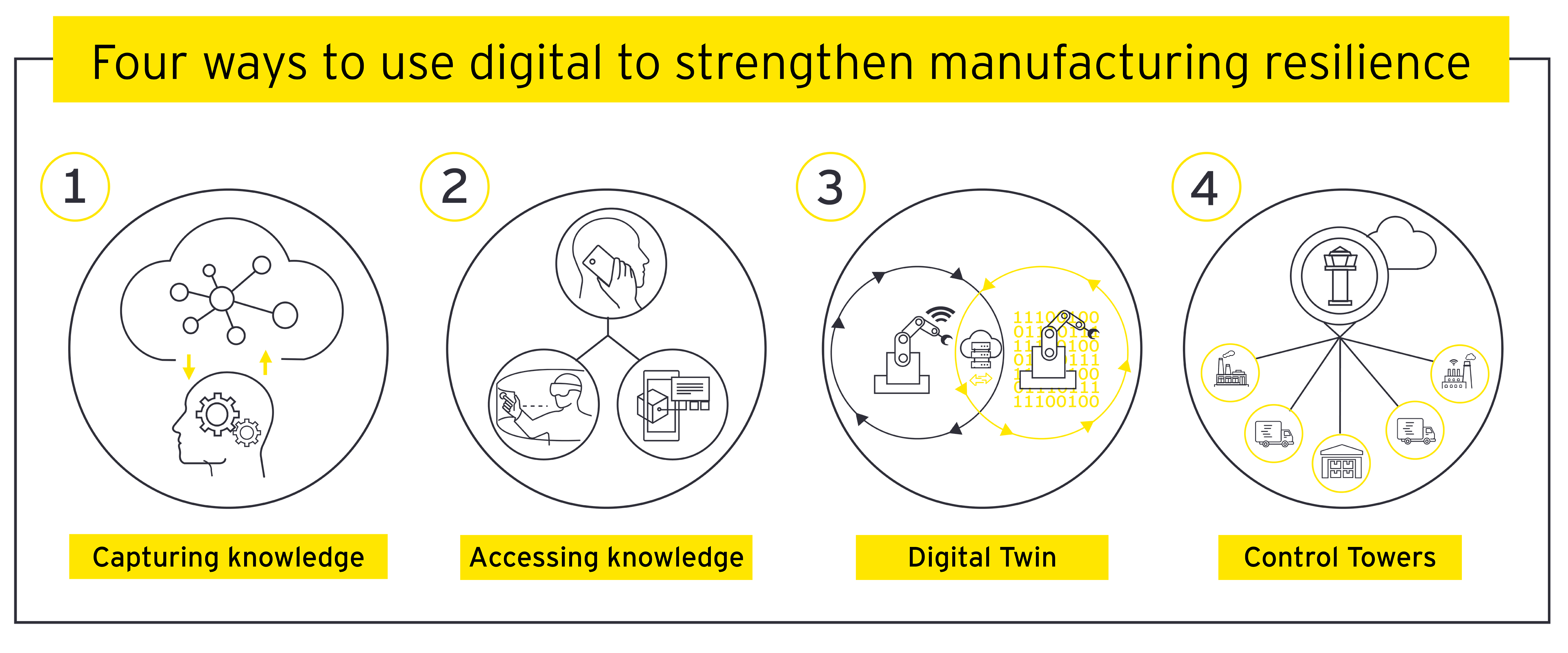

Digital technologies have emerged as a powerful tool for helping manufacturers maintain continuity in the face of major challenges — whether they’re unforeseen ones, such as pandemics or natural disasters, or ongoing systemic issues such as an extreme shortage of crucial talent. A myriad of digital solutions that form the foundation of the smart factory can enable manufacturers to build the resilience they need to minimize the impact of disruptions and maintain effective operations during times of crises. Specifically, digital can help in four key ways:

- Capturing workers’ knowledge

- Enabling better access to expert knowledge

- Speeding decision-making

- Optimizing processes

Capturing workers’ knowledge

In traditional manufacturers, “tribal knowledge” is still widespread. It’s the master tradesman approach: a person has done a job for years and, when not hoarding that knowledge, passes it on to others via formal or informal apprenticeships. This not only keeps the company from more broadly capitalizing on what these experts know, but it also puts the company in the dangerous position of having that knowledge walk out the door as these experts retire.

Manufacturers are trying to get experts to document what they know, but their approaches — which usually center on the written word — aren’t always the most effective or efficient. Take, for instance, the writing of standards. Experts are often asked to develop short written documents that convey how to execute a certain task so that others can benefit from that knowledge. The problem is that it can be difficult to concisely explain an activity comprehensively enough so that it’s useful, but not in too much detail that it might prevent people from actually reading it.

Furthermore, these subject matter experts are generally much more comfortable on the floor “turning wrenches .” They’re not technical writers used to developing such content during the normal course of their jobs, so it can take them several hours to create a single one-page standards documents. The end result: it’s a burden on the experts, who don’t enjoy the task, and it’s hardly the best use of their time and abilities. Plus, the two to three hours an expert spends agonizing at the computer is time that they could have spent creating more product.

Manufacturers can use digital to more easily and effectively capture and convert tribal knowledge into institutional knowledge that stays with the company, and can be more broadly leveraged across the company. Multimedia platforms are now available that enable workers to easily create instructional content of all kind, and in ways that don’t require the written word. Such platforms feature safe, secure and structured databases that can accommodate a wide range of content, including video, audio, written pieces, webcam images, screen captures and hyperlinks.

Instead of having to struggle for hours writing how to change a part on a particular machine, an expert can record a video of the process in only the amount of time it takes to complete the task and upload it to the platform. In our experience, digital tools can reduce the effort to capture knowledge by more than 80% in general, and as much as 95% or more when simple tasks are involved.

Enabling better access to experts’ knowledge

What happens when there’s a problem on the shop floor? A worker needs help from an expert. But what happens if that person is out sick? Who else should the worker call? And once the alternate expert is on the phone, what’s the best way to collaborate with him?

In the typical large manufacturing organization, challenges abound in getting help with an issue, whether it’s not understanding exactly what kind of information is needed, difficulty getting in touch with an expert or even not knowing whom to call to begin with. With experts’ knowledge collected in a formal database, it’s now usable by those who need it, when and where they need it.

Typically, three distinct types of tasks require knowledge transfer. They include:

- Routine and regular tasks — these are tasks that are repetitive and occur with a predictable frequency as a result of the organization’s standard work practices. For these, we can provide simple multimedia instructions linked to the notice of the task.

- Routine and non-regular task — these tend to be more complex, such as product changeover or quality inspections. As routine tasks, they have standards associated with them, but such standards may be a simple checklist without the associated training knowledge. Training in advance through videos (or virtual reality in the future) can eliminate that gap.

- Non-routine and non-regular tasks — these jobs are responses to events rare enough to not have associated standards. A database of structured and unstructured data, as well as digital workflows on problem solving, are best suited for these activities.

By applying intelligence to a database housing experts’ knowledge, a manufacturer can make it easy for workers to get the right information without having to manually search through a sea of data — and potentially miss a document or video that’s key to solving their problem or answering their question. Artificial intelligence (AI) can operate as a sort of “digital coach,” interrogating vast quantities of structured and unstructured data quickly and efficiently to serve up the right expert knowledge to an end user, and eliminate the need to contact an expert directly. In doing so, AI enables manufacturers to get expert data in the hands of people, without having to invest a lot of time and money in distilling all that complex data into information that users can consume.

But sometimes direct expert support is still necessary — the need for it likely will never fully disappear. By also including an inventory of experts in its database, a manufacturer can enable workers to more effectively identify, link to and engage remotely with the right expert. Typically, that engagement would happen via a simple video chat or tool such as Microsoft Teams — for instance — enabling a worker to just turn his phone around to show the expert what he’s seeing and having the expert walk him through the fix.

At some point, we may see augmented reality or virtual reality replace video chat in this scenario. For example, mixed-reality devices, such as Microsoft HoloLens, could enable experts to coach or assist others in different plants or geographies without having to leave their home base — thus, effectively digitally “replicating” those experts and multiplying the impact of their knowledge.