Some useful lessons may be drawn for India’s future economic strategy. First, a decentralized and diffused growth strategy where industrial activities are encouraged to settle away from major urbanized centres such as in smaller sized towns, peripheries of major urban centres and corridors connecting two or more major urban centres may provide a more robust development profile in coping with pandemic type challenges. Second, Atmanirbhar Bharat strategy appears to be well timed since in pandemic type situations, less dependence on global supply chains may be beneficial for minimizing economic damage. Third, expansion of capacity of providing health services as part of overall infrastructure expansion should be taken up on an urgent basis to improve India’s capacity to deal with COVID-19-type health shocks.

Are policy interventions needed at this stage?

Given the lessons from the first COVID-19 wave, and the challenges posed by the surging second COVID-19 wave, policy interventions may be considered from the immediate, the short, and the medium to long term perspectives. In 1Q and 2Q of FY22, the focus has to be on containing the health and the economic dimensions of the second COVID-19 wave. It may be recognized that the longer the second wave lasts, the more severe would be the adverse impact on the economy. There would be a race between the pace of COVID-19 vaccination vis-à-vis. the speed at which COVID-19 including its new mutants spread. In the immediate run, topmost priority should be given to investment in the health sector both for relieving the immediate shortages of vaccines as well as critical COVID-19-related medicines, medical oxygen, and pandemic-earmarked availability of hospital beds.

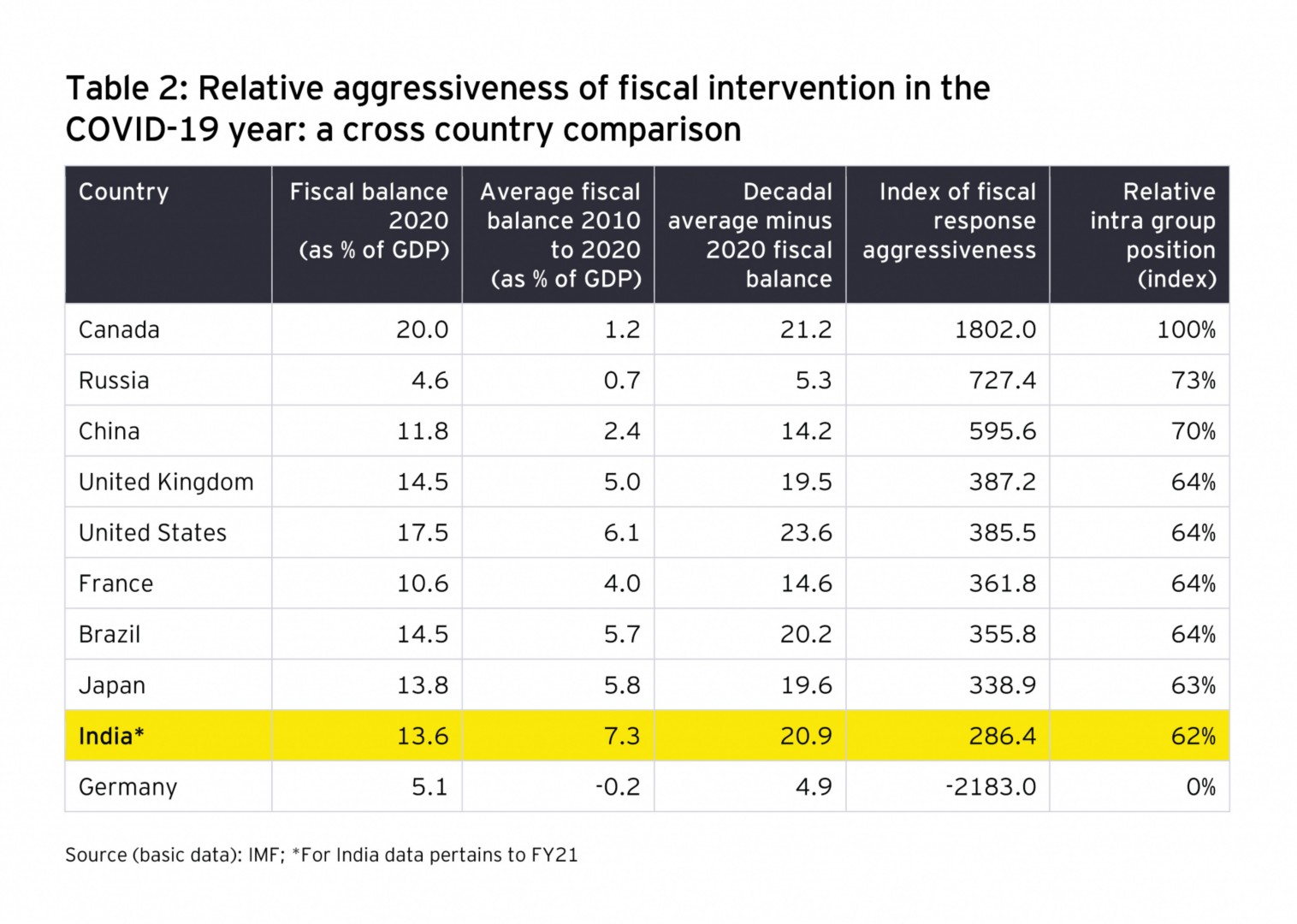

COVID-19 may be considered as a problem that is going to affect the Indian economy at least for the next three to five years. As such, policy intervention should be not only to ameliorate immediate shortages but also to create long-term capacity. Further, beyond the health sector, important economic sectors also require immediate attention. These include, as mentioned earlier, construction, manufacturing and some of the important service sectors. In these cases, private demand may experience a dip and demand may need to be kept up by fiscal and monetary policy stimuli. Here also, the scope for fiscal intervention may be more as monetary policy is likely to remain constrained because of the hardening inflation prospects.

In the context of deficient supply situation with regard to the COVID-19 vaccines as well as some of the important medical inputs including oxygen, a major issue in terms of their inter-state allocation and distribution seems to be developing. Since India has already in place, a framework for fiscal federalism, some useful lessons may be drawn from that experience.

India’s vaccination drive: is there a need for vaccine federalism?

As per the revised vaccination policy announced on 19 April 2021[2] (vaccination 3.0), universal vaccination above the age of 18 years is to be allowed from 1 May 2021. In addition to the central government, state governments and private players have also been allowed to directly access the vaccines from the domestic or foreign suppliers and then according to their own policy, vaccination may be implemented in the respective state. Private firms have also been allowed the same facility. Domestic suppliers will have to pre-announce their prices before 1 May 2021.

Prices for imported vaccines may have to be individually negotiated. These changes will be implemented along with the central government pre-empting 50% of the domestic supply, which will be distributed to the population above 45 years of age as per the existing policy in the government hospitals. Thus, the supply situation may improve with better financial returns for the domestic suppliers and more investment can also take place. There is a lot of ambiguity in relation to the prices that may prevail. With a fragmentation of the market, the possibility of black marketing may also increase. For the 50% of the central distribution across states, the issue of inter-state distribution would still remain and will call for an objective and transparent formula-based distribution mechanism.

The current mechanism of inter-state allocation of the COVID-19 vaccines in India is characterized by non-transparency and ad-hocism. We have ascertained in an econometric exercise that the two main determinants of the inter-state variation in the incidence of COVID-19 in India as measured by the number of COVID-19 cases as a percentage of state population are: (1) share of non-young population in the total population of the state and (2) share of the state in the total population undertaking international travel. This exercise related to India’s 18 medium and large states.

Factors affecting COVID-19 incidence may be divided into two categories, those under the control of the state governments and those that are beyond their control. In the vaccine allocation process, states that are deficient in their COVID-19-containing effort should not be rewarded in the allocation mechanism. Instead, the mechanism can be set in a manner such that states can be incentivised to improve their effort. It may be useful to appoint a high-powered committee to suggest a formula-based transparent mechanism for the inter-state allocation of vaccines just like what the Finance Commission does for the sharing of central taxes.

In the US, the ‘Tiberius algorithm’ has been used for allocating vaccines to the subnational governments wherein the vaccine allocation to a jurisdiction is determined based on its census-derived percentage of population over the age of 18[3]. In India, a recent study by IDFC Institute[4] has quantified an inter-state COVID-19 preparedness index which may also be a relevant factor in the allocation exercise for vaccines particularly when more imported vaccines may be used where facilities for cold storage and transportation may be relevant.

In the medium to long run, as the vaccination process becomes progressively universalized, there may be a need for the private sector and the market forces to play a more active role in the supply and distribution of COVID-19-related vaccines, medicines, and other support services. In order to protect the interest of the low income group, a regulated mechanism of inter-state allocation of vaccine at subsidized prices may need to be continued in the medium-term even as the private sector and market forces are allowed to play a greater role in the procurement and distribution of vaccine supplies.

Conclusion

While the attention of India’s policymakers at the moment is focused on dealing with COVID-19 in general, and its second wave in particular, it would be useful to keep the medium to long term economic prospects and potential of India as the centrepiece of economic policy. In the post-COVID-19 economic universe, most inter-country relationships are likely to undergo major changes. India has to find its rightful position in the new world economic order. The Atmanirbhar strategy has been well-conceived and is quite timely. All efforts should be made to attract investment into India so that India can play a major role in the global supply chains. India will have to compete with China, US, and the EU for attracting investment. In this context, India’s CIT reforms making the CIT rate competitive will become quite relevant. We may also recognize that recently, the US has announced a major stimulus program which includes a long-term plan intended to last until the end of the decade primarily for infrastructure expansion and clean energy worth US$2 trillion which may be financed partially by an increase in the US corporate tax rate from 21% to 28%. If India continues with its current CIT regime, this may have major implications for incentivizing relocation of US investment towards India.

India has embarked upon its own infrastructure expansion plan in the form of the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP), investment in which will continue until FY26. In India’s plan, both the central and state governments including their public sector enterprises and the private sector are to participate. If required, for financing the NIP, the central government may keep its fiscal deficit well above the current FRBM norm of 3% of GDP up to FY26. According to the RBI, the combined fiscal deficit of central and state governments is projected at 10.8% for FY22. Indications are that the central government may improve upon its tax collections in FY21 as compared to the revised estimate. Given the improved revenue performance prospects[5], the central government may do well to frontload its budgeted FY22 capital expenditure in 1QFY22 so as to partially mitigate the adverse economic impact of COVID-19’s second wave.