In our latest issue of EY Economy Watch, we explore why India may witness one of its worst growth outcomes in FY21 despite a historically high fiscal deficit.

World Economic Outlook released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) highlights differential growth prospects in the pandemic year for different countries. India’s growth is projected at (-)10.3% for FY21, one of the worst among major countries, while some of India’s neighbours such as Bangladesh show a healthier potential for growth. This is in spite of the fact that India’s combined fiscal deficit is likely to turn out to be historically its highest. In the In-focus section of the October 2020 issue of the EY Economy Watch, we explore this in depth and argue that this may be due to the pre-pandemic economic challenges. In contrast, before facing the FY09 crisis, the pre-crisis Indian economy had historically the most robust macro parameters.

India’s FY21 growth: unprecedented contraction at (-)10.3%

Considering growth prospects for different countries, with the exception of nine countries, where positive growth is being assessed by the IMF for 2020, all the remaining countries show a contraction. All the important country groups also show a contraction. The Euro area amongst country groups shows the highest contraction at (-)8.3%. The emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) group shows a relatively lower contraction of (-)3.3%. The World economy as a whole is predicted to contract by (-)4.4%. There are four notable countries where contraction is predicted to be more than (-)10.0% in 2020. These are Argentina, India, Italy, and Venezuela. While Argentina, Italy, and Venezuela have often experienced severe economic crisis, India has joined their ranks for the first time. This differential in comparative growth performance may be explained by respective sizes of stimulus packages, differences in the pre-crisis conditions, and other country-specific factors.

India’s fiscal and monetary stimuli: relatively weak in a global context

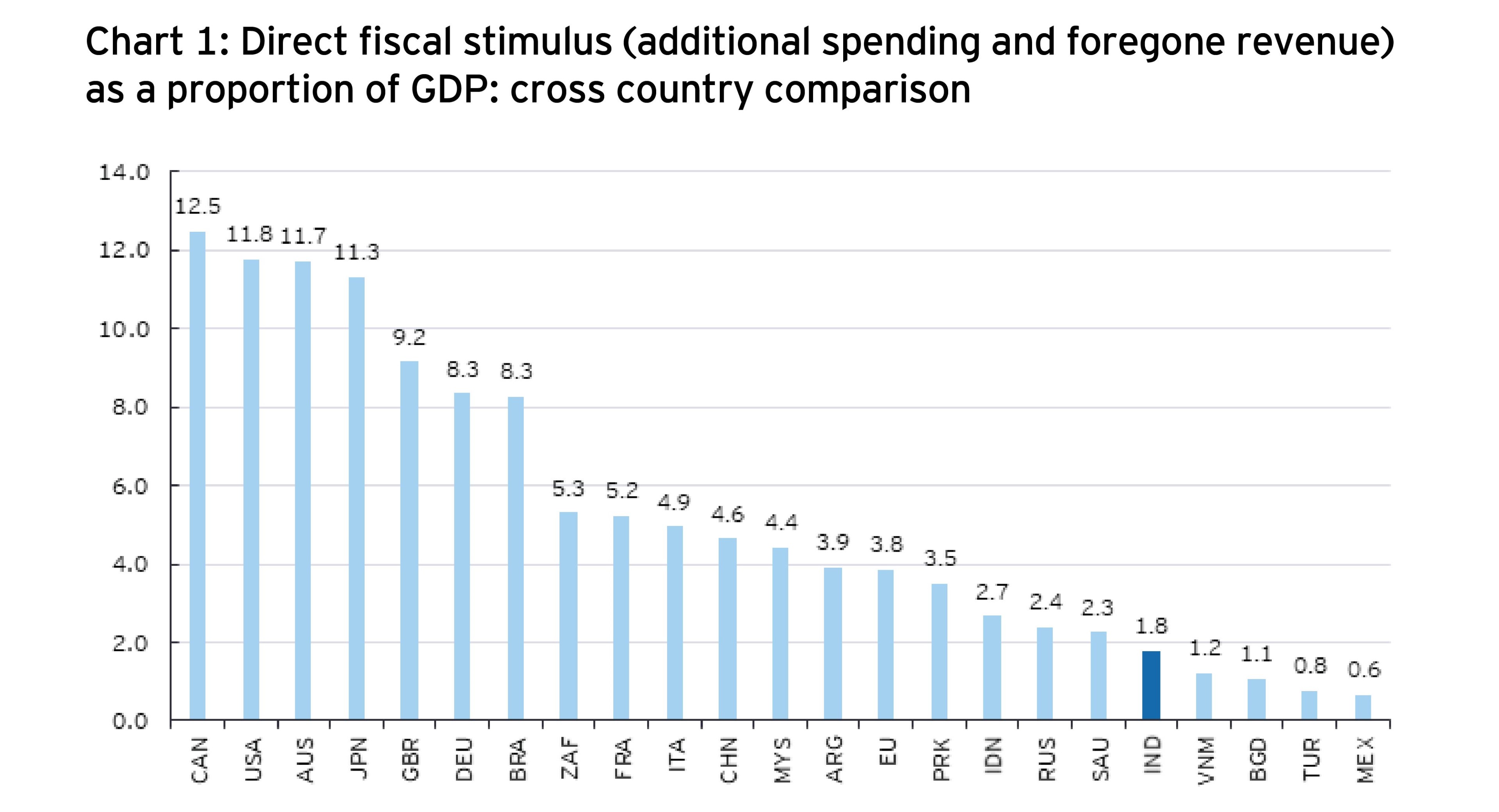

An important indicator of the fiscal support to the economy relates to stimulus measures announced up to September 2020. These measures include additional spending relative to the budgeted expenditures as also the quantified value of tax cuts. A comparative picture as shown in Chart 1 indicates that for India, in spite of the high level of fiscal deficit expected for 2020 (FY21), the direct fiscal stimulus so far in the fiscal year is relatively quite low at 1.8% of GDP. This is because of the expected increase in fiscal deficit just to make up for the revenue shortfall in FY21 so as to reach the budgeted levels of expenditure although some expenditure restructuring may also happen. The highest fiscal stimulus at 12.5% of GDP is for Canada, followed by USA at 11.8%, Australia at 11.7%, Japan at 11.3%, and the UK at 9.2% of GDP. Most European countries have undertaken substantially large fiscal stimulus measures. China’s fiscal stimulus at 4.6% of GDP is more than 250% that of India. Bangladesh is exceptional in the sense that with a limited fiscal stimulus of 1.1% of GDP, it is able to show a positive growth in 2020.