It is time to reconsider India’s macro policy frameworks, not just in the light of their experienced weaknesses but also in view of India’s future needs and compulsions.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, India’s macro parameters have been thrown out of gear. The fiscal deficit on the combined account of center and state governments in FY21 may slip well above 10% of estimated GDP. At the end of FY21, the combined debt-GDP ratio of the central and state government may cross 81% of GDP, more than 20% points above the targeted threshold of 60% as per center’s revised Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act (FRBMA) of 2018. The CPI inflation rate crossed the 6% upper tolerance limit of the monetary policy framework (MPF) in 4QFY20 and 1QFY21 and may remain close to 7% in the near future. In fact, India’s economic crisis predates the pandemic. The weaknesses of the FRBMA and the MPF had already started becoming visible with FY20 real and nominal GDP growth rates plummeting to debilitatingly low levels of 4.2% and 7.2% respectively. It is high time that we consider recasting India’s macro policy frameworks, both fiscal and monetary, not only in the light of their experienced weaknesses but also considering India’s future needs and compulsions. This issue is discussed in detail in the In-Focus section of the August 2020 issue of the EY Economy Watch.

Infirmities of center’s 2018 FRBMA

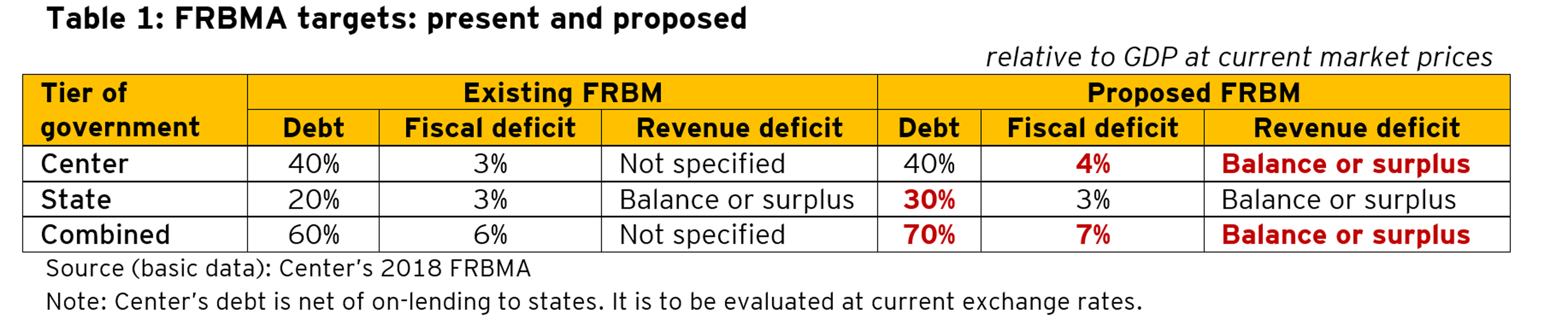

With the combined debt-GDP ratio likely to depart from the target level of 60% by more than 20% points at the end of FY21, it would render the 2018 amendment to the FRBMA completely out of alignment. In fact, the 2018 FRBMA has a number of other infirmities:

- Elimination of revenue deficit target: Maintaining balance or surplus on revenue account is critical since it is linked to government sector dissaving. For realizing India’s potential growth, it is critical to maximize the savings rate. One important instrument for this is to maintain government’s revenue account in balance or in surplus. This was also the primary objective of center’s 2003 FRBMA. The target of maintaining a revenue account balance has been given up in Center’s 2018 FRBMA.

- Inconsistent targets for debt and deficit for center and states: Maintaining a fiscal deficit target of 3% of GDP for both center and states is inconsistent with targeting debt-GDP ratio of 40% for center and 20% for states. Simulations indicate that debt-GDP ratio for center and states should be equal if their fiscal deficit targets are equal.

- Inadequate countercyclical clauses: Center’s 2018 FRBMA has a provision for countercyclical measures. It provides for five conditions under which a departure from the operational fiscal deficit target of 3% of GDP can be made. These conditions relate to: (a) national security, (b) act of war, (c) national calamity, (d) collapse of agriculture severely affecting farm output and incomes and (e) structural reforms in the economy with unanticipated fiscal implications. The COVID-19 pandemic may be classified as a national calamity under clause (c) above. However, in a pandemic like situation, the magnitude of permitted departure has proved to be too inadequate. Further, the 0.5%-point departure rule has also proved to be too impractical to capture the evolving situation.

Infirmities of the monetary policy framework

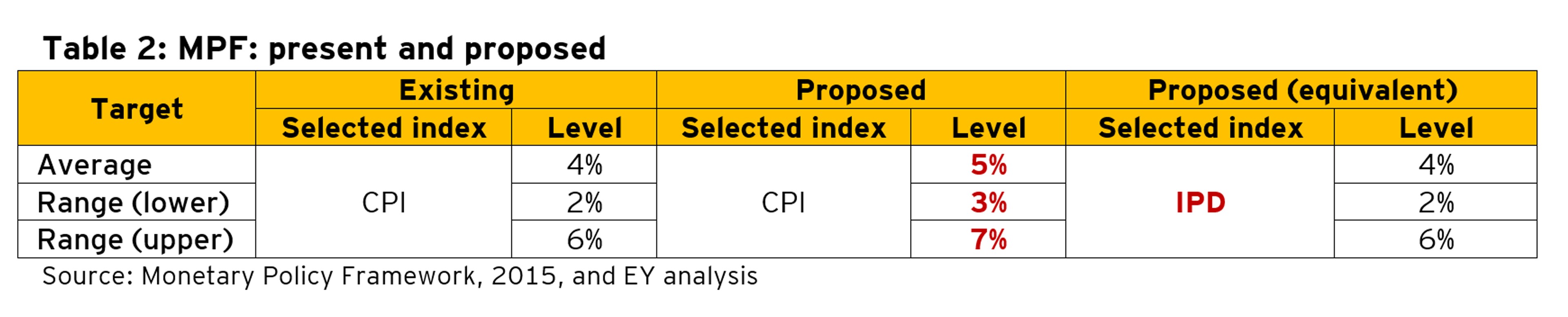

There are two important deficiencies in the monetary policy framework in the current Indian context. First, there is no emphasis on the growth objective for the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to consider. Second, the CPI inflation target of 4% on average implies an IPD-based inflation of 2.5-3%. This is too low and inconsistent with the fiscal policy framework which assumes a nominal GDP growth of 11-12%.

In the case of fiscal policy decisions, two implicit assumptions regarding nominal GDP growth are important. First, with respect to GST, the states were guaranteed a growth of 14% in nominal terms in their GST revenues. This guarantee was implemented through the mechanism of the compensation cess. A 14% growth in GST revenues assumes a combination of GST buoyancy and nominal GDP growth. A buoyancy of 1.2 for the component of GST attributable to states (SGST + states’ share in IGST) implies a nominal GDP growth of 11.7% per annum. The Union Budget FY18 had also assumed a nominal GDP growth of 11.75%. According to the minutes of the 3rd GST Council Meeting held on 18-19 October 2016, most state ministers had argued for a 14% growth over the base year GST revenue, considering a nominal GDP growth of 12% or above. Second, for stabilizing the combined debt to GDP ratio at 60% with a 6% combined fiscal deficit-GDP target as per center’s 2018 FRBMA, the implicit nominal GDP growth rate works out to be nearly 11%. These growth assumptions turned out to be much higher than the nominal GDP growth outcome driven by the MPF. The MPF targeted a CPI inflation of 4%. The IPD based inflation during FY15 to FY20 was below the CPI inflation by 1.2% points on average. This implies that a CPI inflation target of 4% was associated with an IPD based inflation of 2.8% during FY15 to FY20. Combining the average IPD based inflation at 2.8% with the average real GDP growth at 6.8% during FY15 to FY20, the resultant nominal GDP growth comes out to be 9.8%. Thus, there is a built-in inconsistency between the two macro policy frameworks.