Obstacles and opportunities on the road to renewable energy expansion

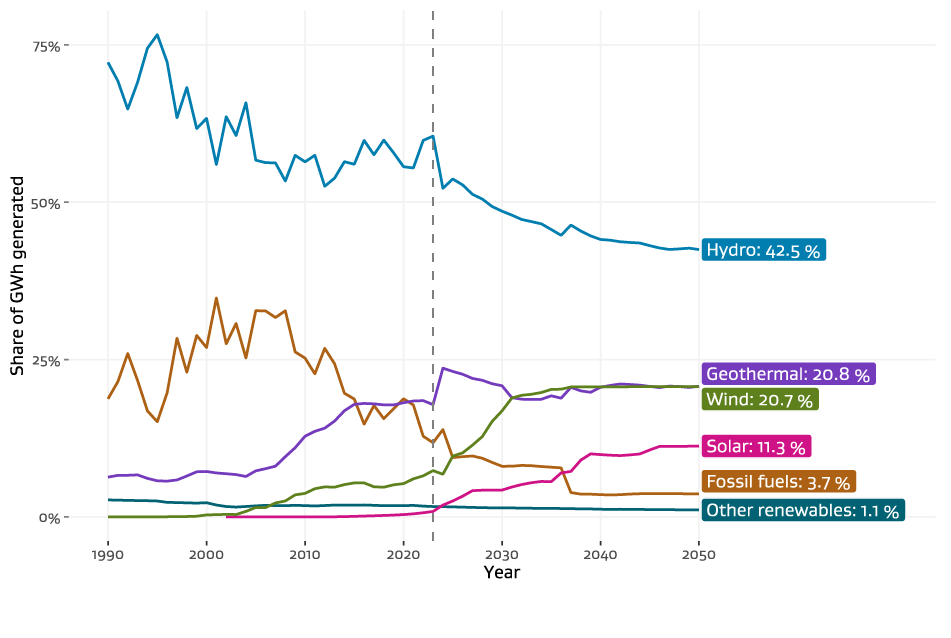

While New Zealand’s electricity is clean, that doesn’t mean it is cheap.

New Zealand’s electricity market is a small ecosystem dominated by a handful of players. In recent years, uncertainty around the fate of New Zealand’s only aluminium smelter at Tiwai in Southland, which consumes around 13% of the nation’s electricity, has stifled market confidence and the enthusiasm of investors.

New Zealanders are paying the price for this lack of investment. Uncompetitive electricity costs have hurt consumers’ hip pockets and could potentially discourage large tech companies from growing their data centre footprints here.

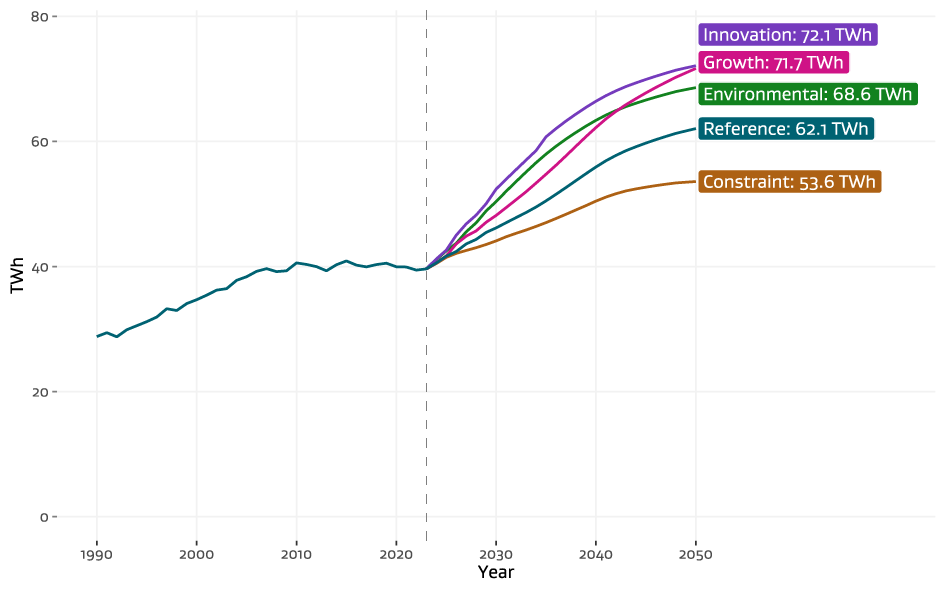

But in May 2024 the owners of the aluminium smelter struck new agreements which secure energy supply from three generators until at least 2044. This provides demand certainty for the roughly 5 TWh of energy required annually to run the smelter and creates the long-term demand stability required for new investment into energy projects.

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment has estimated the country’s data centre load could reach around 4.6 TWh annually by 2035 – roughly the same amount as the smelter. With the aluminium smelter’s energy consumption locked in for 20 years, New Zealand must rapidly expand its energy supply to seize the strategic advantage of its suitability for AI.

Addressing barriers to bridge the sustainable computing gap

New Zealand’s many natural advantages are tempered by a notable downside: the tyranny of distance. For certain AI applications, physical proximity is crucial. A user who is 10 kilometres away from an AI application’s servers, for example, will receive their search response much faster than one 1,000 kilometres away. However, we can address this challenge by assigning tasks where latency is less critical, such as in training large language models (LLMs). If LLMs need updating on a more regular basis in the future, New Zealand’s data centres could provide these services while large markets like North America and Europe are asleep.

Other barriers, such as the high cost of electricity and the lack of water infrastructure, are not as easily remedied. Infrastructure New Zealand estimates that up to $185 billion investment is required over the next 30 years to bring the country’s water infrastructure up to scratch.

For New Zealand to lower its energy costs and improve its water infrastructure, the country needs to attract international capital. If private investment into growth areas, such as AI and data centres, can be strategically structured, this could provide part of this much needed capital injection. Sustainable finance structures could support data centres to access the renewable energy profile they require, provided the data centres provide investment into New Zealand’s water and energy systems and create local demand for low-carbon construction products. In turn, this would provide broader economic benefits through lower-cost energy, improved water infrastructure and new low-carbon growth industries for New Zealanders.

Focussing on our strategy advantage can drive growth and jobs

Forecasting the future of AI is challenging, as it is hard to see where the upper limits of growth lie. Bloomberg has predicted generative AI alone could expand to US$1.3 trillion market by 2033, with a compound annual growth rate of 42%.

The AI explosion is an unmissable economic opportunity for every country that identifies and capitalises on their strategic advantage. New Zealand currently has data centres, mostly clustered around Auckland and Wellington. But there is no reason why we can’t strategically scale sustainable data centres around the country, creating jobs and stimulating economic growth during construction, securing highly specialised, high-paying jobs during operation and attracting international capital looking to invest in commercial real estate and infrastructure development.