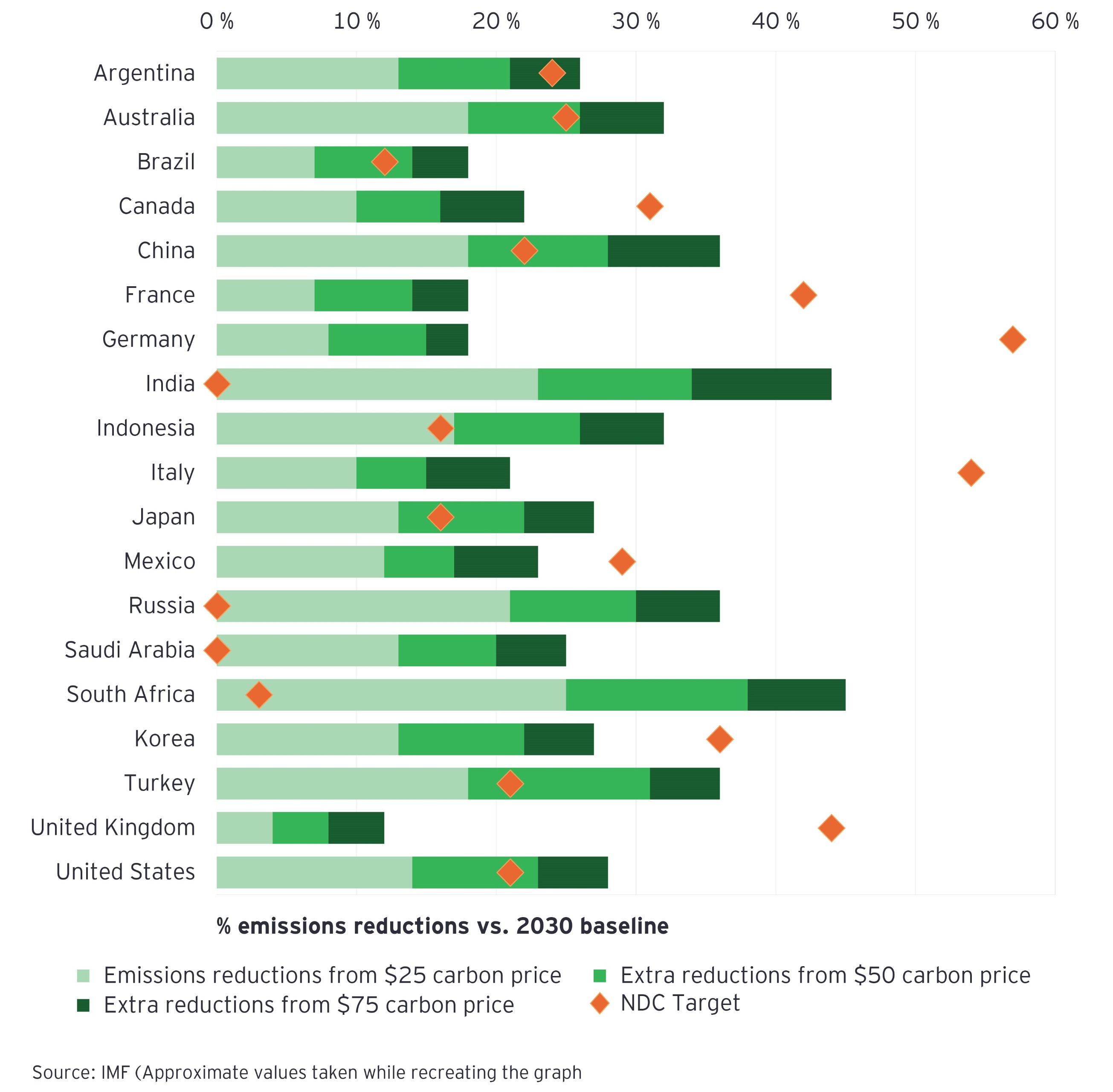

One of the popular policy options to reduce carbon emissions is setting a price for carbon through trading schemes or by implementing carbon taxes. Until now, India has relied on the former. For instance, electricity distribution companies are required to mandatorily source some amount of renewable energy. Similarly, government has mandated the usage of CNG for public transport. Incentives to electric vehicles and prescribing codes for greener buildings are among the regulatory measures recently used to reduce emissions.

A carbon price applied directly or implicitly to carbon emissions can be effective in reducing emissions by increasing the price of high-emissions inputs. Businesses that seek to maximize profits respond to high input prices by finding ways of limiting the use of such inputs and reducing the production of products causing pollution.

Explicit price of carbon emissions can be achieved both through carbon trading schemes and carbon taxes. In a carbon trading scheme, the government sets a cap for the level of permissible emissions. It then gives emission allowances to entities, where the total allowances equal the cap. Entities can buy and sell these allowances based on their needs and the secondary market reveals the cost of emissions. Therefore, like carbon taxes, a carbon trading scheme also provides a transparent and tangible cost of carbon emissions. However, prices for carbon trading can often be volatile as they are driven by forces of supply and demand. In contrast, carbon taxes provide greater certainty to businesses regarding the price that must be paid for emissions. Certainty in pricing helps players make better decisions about technology and usage choices.

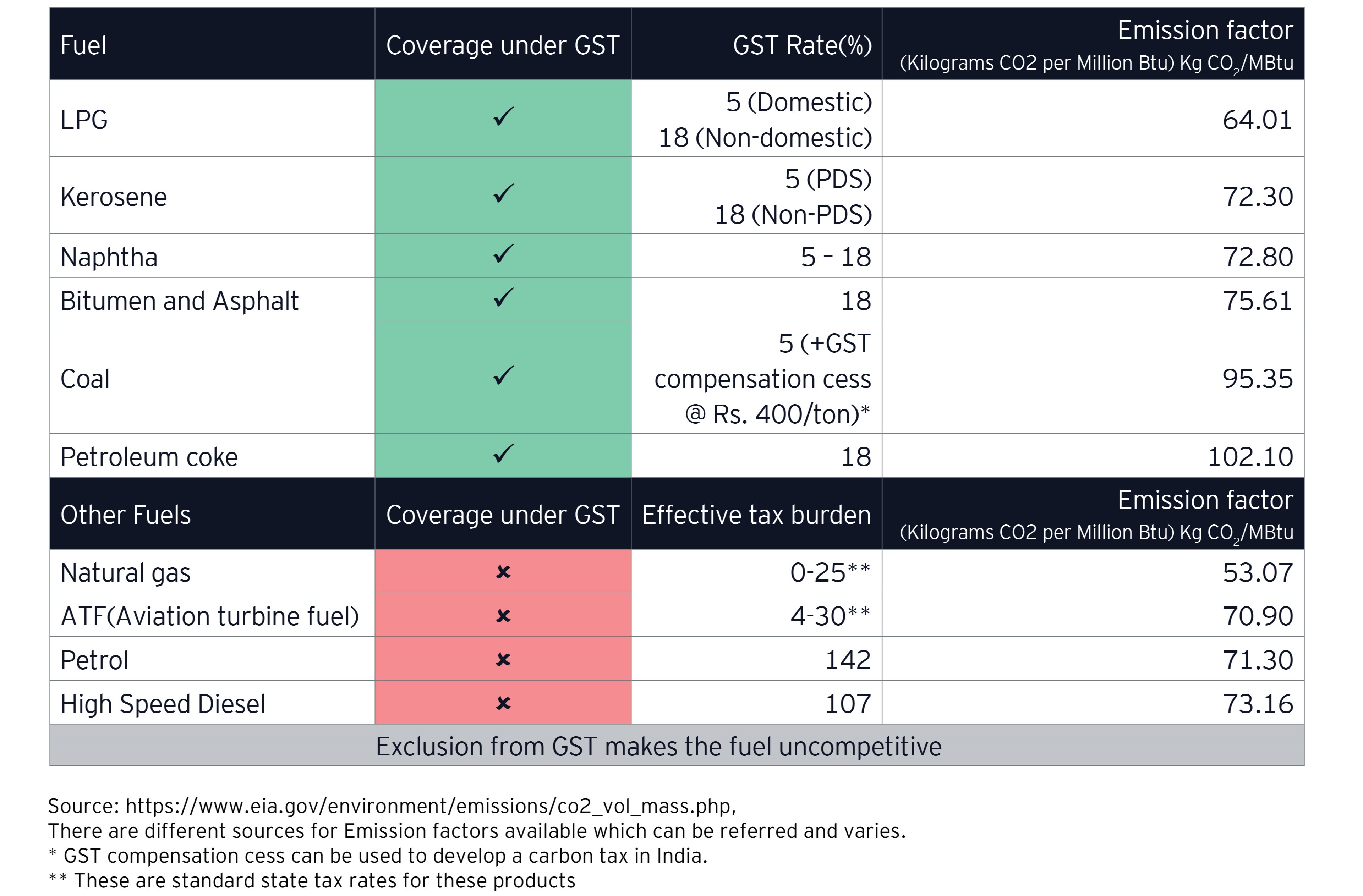

In India, the coal cess of Rs 400 per tonne and the high level of taxation on petrol and diesel are examples of an implicit carbon tax. Currently, effective tax on petrol and diesel is in excess of 100% in contrast to the general 18% tax on most fuels subject to GST. However, India does not have an explicit carbon tax[1]. Also, clean fuels like natural gas continue to be outside the ambit of GST, impacting their competitiveness and India’s ability to reduce emissions. Thus, even though some of the levies are in the nature of a carbon tax, the overall taxation structure in India does not seem to be designed to provide incentives to reduce emissions. The table below depicts that the tax treatment of fuels in India is not related to carbon emissions.