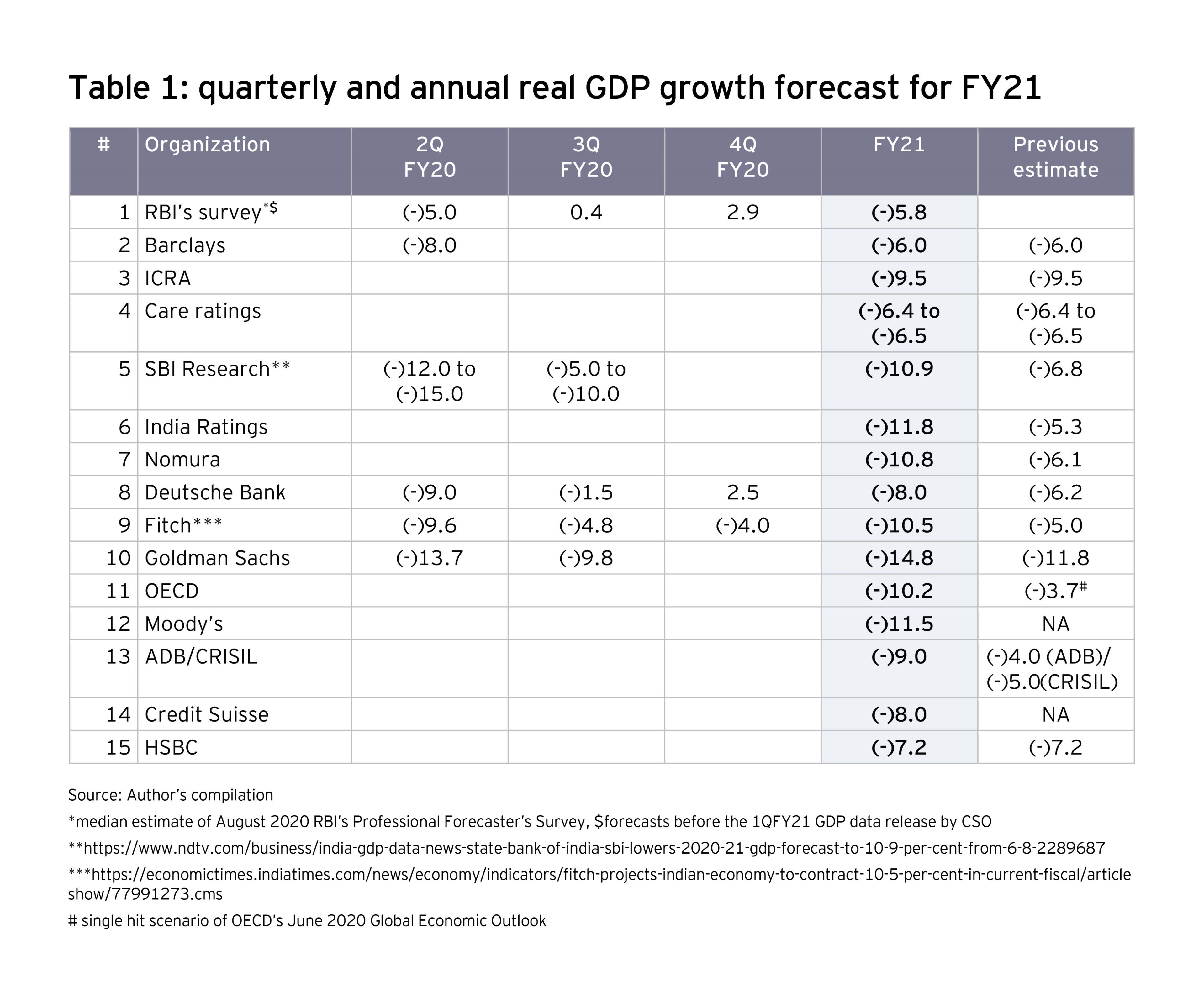

In the quarterly forecasts, the turnaround to a positive real GDP growth is seen only in 4QFY21 as per Deutsche Bank while the RBI’s Professional Forecasters Survey predicts a positive turnaround in 3QFY21.

The annual projections also indicate the strong likelihood of even the nominal GDP growth showing a contraction in FY21. If we take OECD’s real GDP growth projection for India at (-)10.2% and a deflator-based inflation of about 5%, the implied contraction in nominal GDP comes to about (-)5.0%. A contraction in nominal growth also indicates a contraction in the tax revenues of the central and state governments. This highlights that the key instrument available with the central government for turning around the economy in the current and the next year is an exceptionally high fiscal deficit.

Fiscal deficit prospects: finding resources for next round of stimulus

Current fiscal trends indicate that the main route through which fiscal stimulus can be injected is augmentation of fiscal deficit of the central and state governments. The states have been allowed an increase in their aggregate fiscal deficit from 3% to 5% of GDP. The additional borrowing of 2% of GDP can be divided into two parts. Up to 1% is linked to incentive-based borrowing with respect to four conditions. The balance of 1% of GDP has been linked to GST compensation cess where the states have been given two options. In option 1, if all states opt for it, the upper limit of borrowing would be INR97,000 crore which may be marginally less than 0.5% of estimated FY21 GDP. Individual states can exercise this option and their borrowing may amount to about 0.5% of their respective GSDP depending on their share in the aggregate amount under option 1. Any state going for option 1 will be allowed another 0.5% of GSDP as unconditional borrowing. In option 2 also, states can access up to 1% of their respective GSDP related to four incentive linked conditions. Further, they can opt for borrowing their full share of the aggregate shortfall of INR2.35 lakh crore. If all states go for this option, their aggregate borrowing would be slightly in excess of 1% of estimated FY21 GDP. However, states going for this option will not be allowed the additional unconditional borrowing and bonus tranche together amounting to 1% of their respective GSDP. 21 states[1] have opted for option 1. Other states have rejected both the options and called for Prime Minister’s intervention. The situation will become clear in due course. For the time being we can consider 5% as the upper limit of the state borrowing in FY21. In both the options, the borrowing related to the shortfall in the GST compensation cess will be reimbursed to the states by the extension of the cess beyond the transition period.

As per center’s borrowing program announced on 8 May 2020, the targeted borrowing amounts to INR12,00,000 crores. This would be about 5.9% of GDP if we keep nominal GDP at the FY20 level implying a nominal growth of 0% in FY21. If the year ends in a contraction in nominal GDP, center’s fiscal deficit to GDP ratio would be higher.

Any additional stimulus will call for further increase in center’s borrowing. A combined borrowing by center and states of 12.5% of GDP or above may require a substantive portion of the borrowing being monetized by the RBI directly or indirectly, thereby increasing pressure on inflation.

Concluding observations

Being a pandemic year, FY21 should be considered as an exceptional year outside of the normal growth path of the Indian economy and the path of fiscal consolidation. A combined fiscal deficit of more than 12% of GDP would need to be corrected afterwards. But the pandemic’s shadow may last for one or two more years. The fiscal correction should be gradual so that growth is slowly nursed back to India’s potential. In FY22, combined fiscal deficit may be kept at 9% of GDP and FY23 onwards, it may be sustained at 7% of GDP. The combined debt-GDP ratio would take much longer to be brought down from its anticipated level of about 90% by the end of FY23 (World Bank). It may also be worthwhile recasting India’s fiscal and monetary policy frameworks, an issue that was discussed at length in the ‘In focus’ section of August 2020 issue of Economy Watch.