Chapter 1

Why Government needs to personalise digital services

Citizens are becoming more discerning and looking for sustainable digital transformation of government services rather than short-term fixes.

One of the most striking consequences of the pandemic has been our increasing reliance on everyday technology, from online shopping to virtual workplaces. This momentum provides the impetus to sustain the trajectory of digital transformation, where we now see technology as instrumental in improving many aspects of our lives.

But while governments around the world have accelerated the digitisation of many public services, the citizen experience continues to lag services provided by the private sector, such as online shopping and banking, in terms of expected improvements and personalisation.

The good news is that Australians are increasingly receptive to the use of technology by government and have taken notice, with almost two-thirds believing the government and public service’s use of technology to respond to the pandemic was effective.

Citizens are also becoming more discerning and looking for sustainable digital transformation of government services rather than short-term fixes through shiny new apps that are not integrated or that deliver limited value. The use of QR codes and payment via your phone or watch has become commonplace during COVID-19. These accessible approaches need to be expanded and move to the next level of sophistication for other servicing.

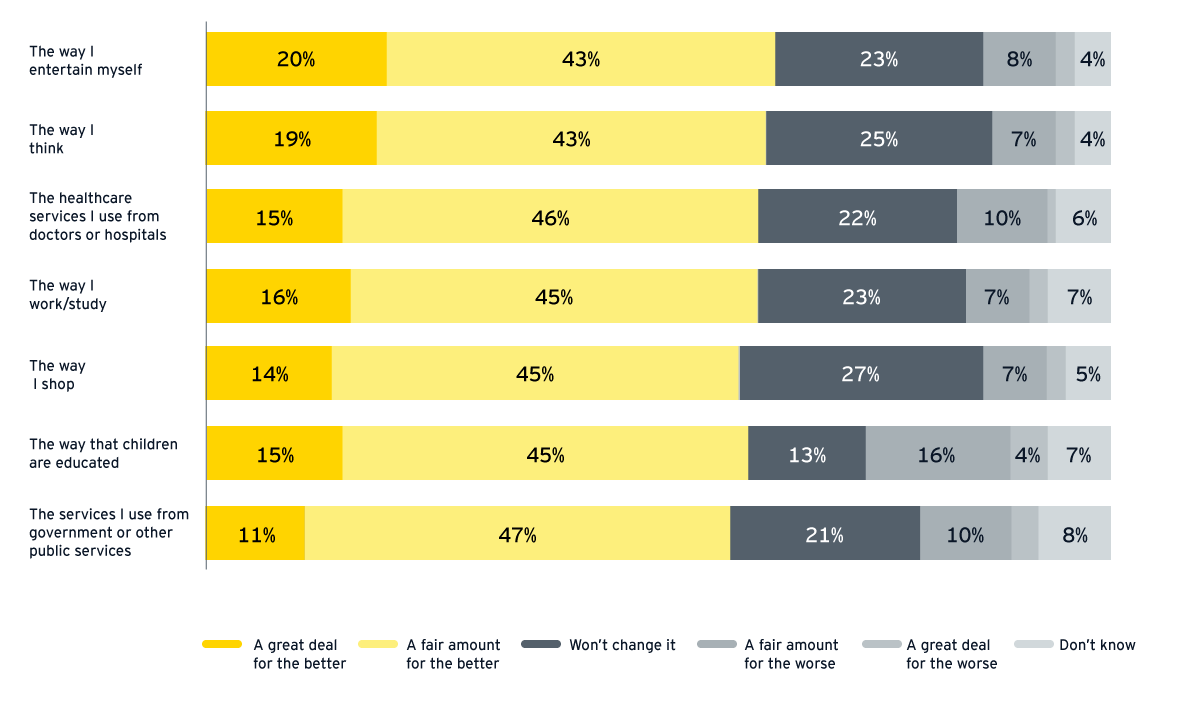

Technology is expected to improve how people manage many different aspects of their lives ... but public services lag behind other sectors

Question: Looking ahead to the future, to what extent, if at all, do you think technology will change the way you do each of the following? Is that for better or for worse?

As well as exploring in detail how citizens use and engage with technology (see our comprehensive report on the survey), the data has helped uncover seven different citizen personas that governments should understand in order to deliver effective digital services in the future: Diligent Strivers, Capable Achievers, Privacy Defenders, Aspirational Technophiles, Tech Sceptics, Struggling Providers and Passive Outsiders.

These personas bring to life a citizen-centric approach and provide a useful springboard to help design and deliver on the ambition of a digital government within the broader context of a digital economy.

Chapter 2

Embracing the opportunity in different citizen groups

Understanding these personas can help governments build a more trusted relationship with citizens.

While the different personas share many characteristics, governments need to be aware of and respond to key differences between each of the personas. These personas will be informative in designing and transforming government service delivery models that balance experience, cost to serve and outcome effectiveness while ensuring equity is not compromised.

In Australia, the largest Connected Citizen group are the Capable Achievers, at 23% of the population, giving governments a clear opportunity to work with a cohort who actively embrace digital innovation. Four groups hover around 15%, while Passive Outsiders and Struggling Providers are lower at 10% and 8% respectively.

In Australia,

23%of the population are Capable Achievers.

8%

of the population are Struggling Providers.

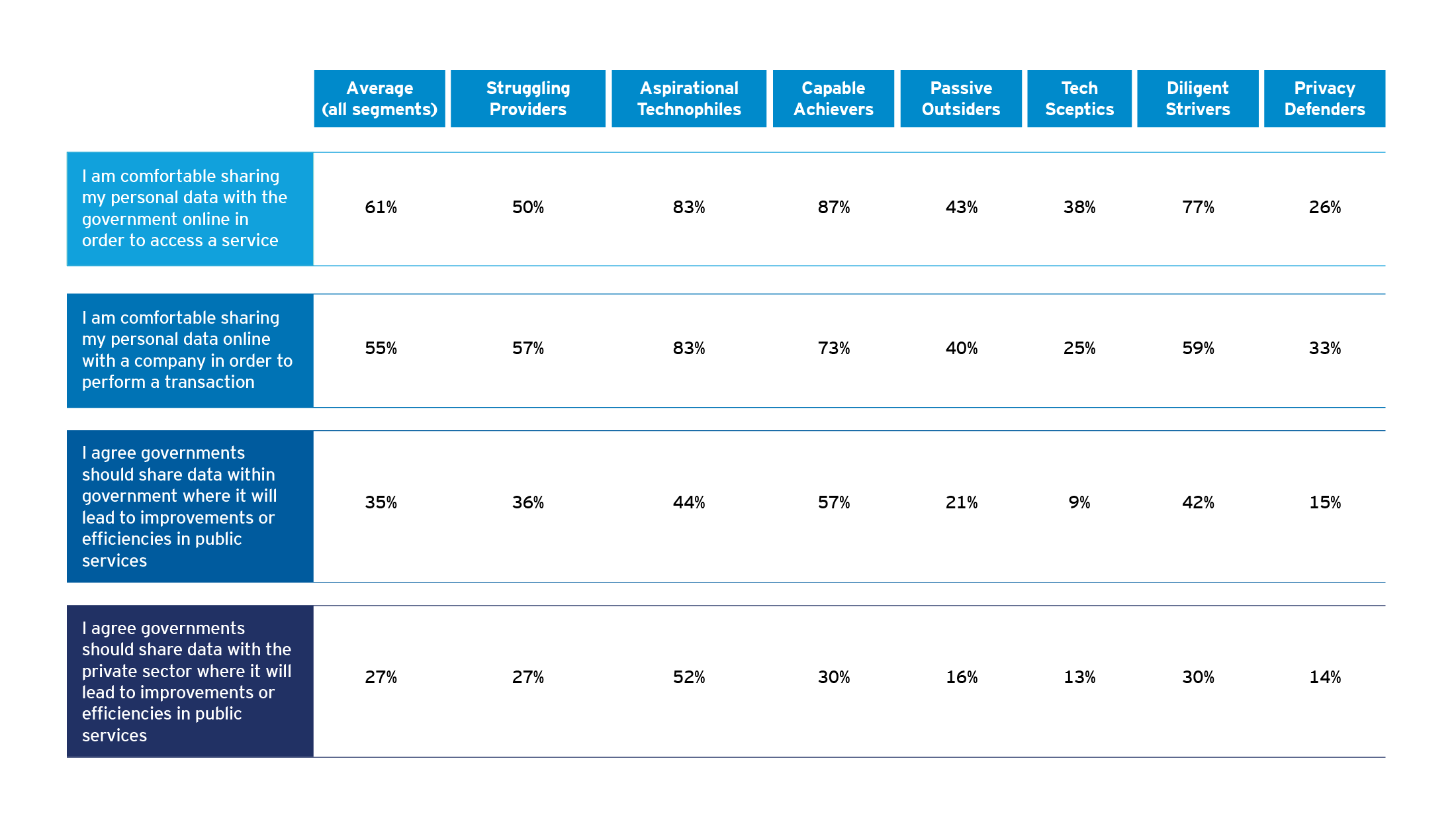

These basic insights tell us that it’s not just the use of data that is important. It is also the responsible use of citizen data that government needs to address. And through responsible data use, governments can start to establish trust.

At the same time as citizens start giving more permission to hold and use their data for increased service delivery, consent-based systems and principles will need to be standardised and streamlined. Citizens expect that their information is enabling the intended outcomes and any unintended consequences are managed and mitigated.

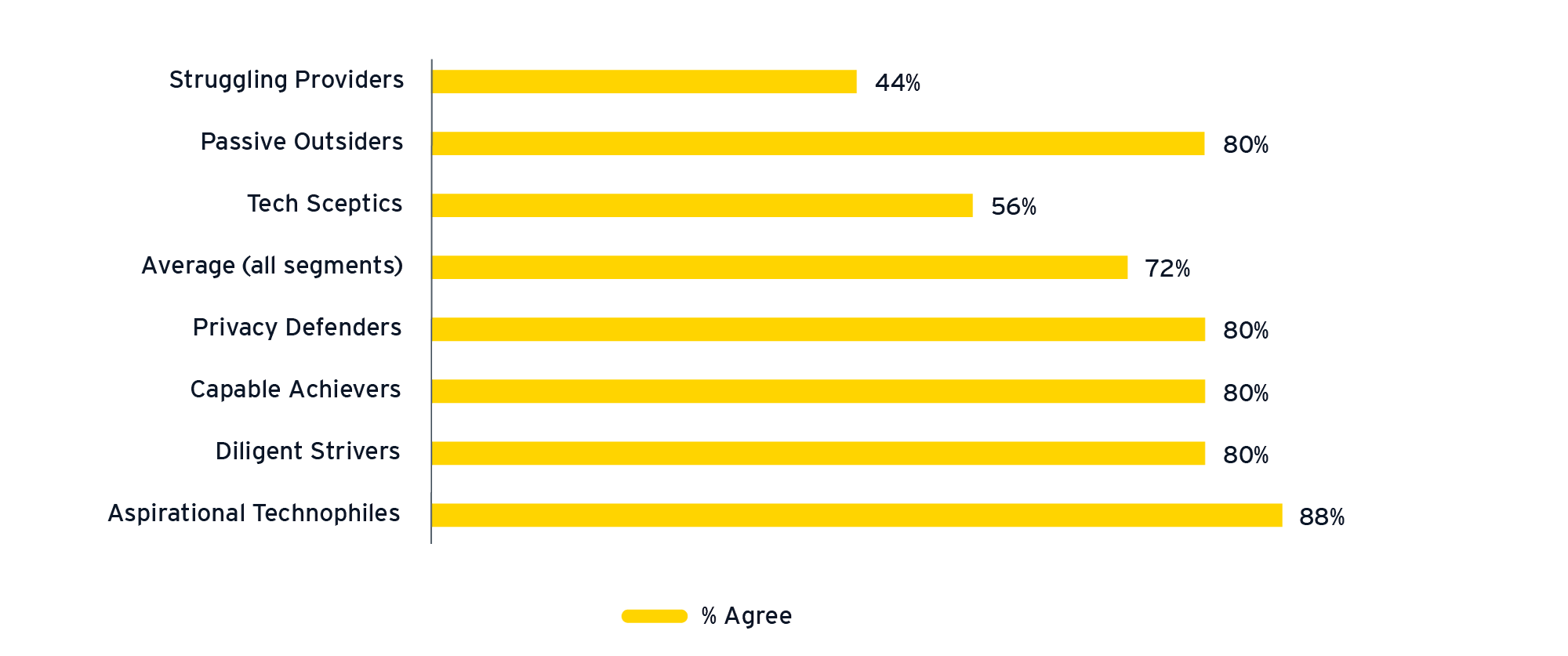

A striking difference between the personas is their attitudes to technology and digital service delivery, with less than half of the Passive Outsiders and Struggling Providers group saying they feel comfortable using new technology on their own. While they each represent a relatively small group, taken together these two groups make up almost one fifth of the Australian population, strongly suggesting a targeted program to lift Australia’s digital capability will be needed.

Similarly, people have strongly diverging attitudes toward sharing data. While some groups are comfortable sharing data to access a service or perform a transaction online, others voice real concerns about the risks involved. The need for governments to maintain citizen trust with data consent privacy issues will be a key success factor for the continued growth of the digitally connected citizen in Australia.

The key point emerging from the survey is that Australia’s citizens have a higher willingness and capability to use digital services. However, we are on the lower end of trusting our government with our data. This means that government needs to overcome the hurdle of trust if it is to be successful in its digital transformation.

Some of our citizen segments lack the confidence to use new technology

Question: To what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement about technology? - I feel confident using new technology on my own

Why does this matter? Almost one-third of global citizens rank more use of digital technologies in public service provision as one of the top three priorities for governments to improve service quality. So as governments move towards “digital by design” and “digital by default” approaches to service delivery, these personas can help governments ensure that digital services and data policies are properly designed across these different cohorts.

For example, what happens to the Struggling Providers — who may need the most support — if digital channels are the only way to access some services? Could they miss out on services and opportunities, and see the structural inequality they suffer from get worse?

Greater personalisation will help improve public policy design, deliver more efficient and effective public services, and strengthen the relationship between government and citizens.

The citizen-centric approach will also shift the role of government beyond just being a regulator and service provider. Government will now need to become a participant in and facilitator of the digital economy.

In addition, as government services are extended and transformed, organisations rolling out these changes must establish and maintain trust with citizens, particularly with respect to data privacy and consent. An example of government leaning in to these innovations is the Consumer Data Right (CDR) program that went live on 1 July 2020. Implemented by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, the CDR allows consumers to “share their data relating to home loans, investment loans, personal loans and joint accounts” while ensuring that strong privacy protections are built-in and enforced. While the focus has been on financial services in the first instance, the CDR program is in line to be rolled out to other sectors such as energy and utilities.

Chapter 3

Three priorities for governments

Taking steps to meet the needs of citizens and engage them as co-producers of public value.

Policymakers should focus on three priorities as they strive to meet the multi-dimensional needs of citizens, engage them as co-producers of public value and deliver more effective and efficient digital services.

1. Trusted inclusive digital service delivery

Inclusive digital service delivery makes sense if it is framed around a new model of customer engagement. If government is going to solve the high capability versus low trust problem in Australia, inclusive and trustworthy systems will also need to be implemented and enabled.

Governments need to embark on a digital transformation program that focuses not just on how services are delivered, but also on what services are delivered. What’s required is a reshaping of public services enabled by technology, designed from the citizen’s perspective and on par with or better than private sector services. This is the way to create public services that are differentiated yet inclusive, leaving no group behind.

A priority will be investment in high-speed digital infrastructure, including broadband and 5G networks, to provide connectivity in all parts of the country. With our nation lagging the digital infrastructure of many other developed countries, this is one of the critical challenges Australian policymakers need to urgently address. Governments can also help provide devices (like laptops and tablets) to get people online and run programs to improve people’s digital literacy so they have the skills and confidence to interact with digital services.

But governments will also need to ensure that those who are not digitally connected have alternative ways of accessing services. The requirement for no citizen to be disenfranchised is a major consideration for all public services.

Citizens already confident with technology have heightened expectations for service delivery, in terms of quality, speed, convenience and value for money. Governments will need to work to meet the expectations of these citizens, applying private sector standards. For example, now that the CDR has impacted expectations of how services are delivered to consumers, the Australian Government will also need to implement CDR for ‘Government-to-Citizen’ services.

Examples of digital services and their implementation:

- Transparent data privacy, security and consent measures to establish and maintain trust in service delivery.

- Unique digital credentials that allow citizens to gain easier access to a range of services through multiple digital channels.

- Increasing the use of biometric data to facilitate more effective movement and access to services supported by trusted identity validation and verification of people.

- Smart portals and mobile apps that provide one-stop access to multiple government services, as well as pushing timely messages and updates. Integrating these across levels of government should be the ultimate goal.

- “Tell-us-once” services so people don’t have to re-fill their personal data online for different government transactions and, over time, extending this across Federal, state and local government levels so that government operates as one intelligent, integrated system designed around the citizen (and businesses).

- Integrated digital platforms that enable data sharing across different government systems, creating a complete view of the citizen and organising services around people’s needs and life events.

- Smarter infrastructure and buildings that are IoT (Internet of Things) enabled providing intelligent cities to citizens.

- Full, digital end-to-end fulfilment of service requests that enable speedier delivery.

- Conversational platforms, with AI-powered chat bots, to interact with citizens, rapidly resolve queries and complete transactions.

- A true omnichannel experience, allowing people to access services on a variety of platforms using a range of devices that is AI enabled where possible.

- Use of digital and emerging technologies to manage peak customer interaction volumes and delayed response times onset by disasters or emergency situations, enabling staff to focus on engaging with citizens that have unique or specialised circumstances.

Design thinking, customer experience labs and data analytics will help governments design their services to make each touchpoint better, faster and more efficient. The eventual goal is proactive and even predictive service delivery embedded in natural systems, where possible, reducing the administrative and compliance burden. This will ultimately free up resources to focus on those that need it most – the vulnerable in our society.

2. Responsible use and sharing of data and information

We’re producing and storing more data than ever before and now have the tools to analyse the data for the public good. And while most people believe data analysis and technology will be needed to help solve increasingly complex future problems, they are concerned about widening social inequality, loss of human interaction and the potential encroachment on personal privacy and digital security.

Within a digital economy, it’s the role of government to support and enable interoperability of services while giving citizens a single pathway to access all those services. Initiatives are underway to provide visibility of data standards across government and to inform decision-making that drives interoperability and frictionless, seamless data sharing across government and business.

Governments also need to step up their involvement in collaborative information sharing programs so that there is a common understanding of not only what systems are used but how all the information is gathered and shared. The ultimate goal should be the ability of citizens to access one single multi-jurisdictional channel for their service delivery.

There is an opportunity for further data sharing across all levels of government in Australia that focusses on, at minimum, a “tell-us-once” approach. This approach works on the principle that information provided in one part of government can persist across multiple agencies, jurisdictions and programs. For example, integration between services for vulnerable people in Australia could see Federal health agencies interacting and sharing data with the Department of Health and Human Services in Victoria, Service NSW and the Department of Communities and Justice in New South Wales.

New regulatory, legal and governance frameworks are, however, needed to both capitalise on the opportunities and manage the potential risks for citizens. For instance, policymakers will need to take a hard look at issues such as data privacy, surveillance technology, the inequities embedded in algorithms, how organistions are using data in their AI systems, and the integrity of the information ecosystem.

Australia is well underway to deal with privacy and consent-based systems such as CDR. Governments are already strengthening regulations governing the use of people’s personal data, creating legal frameworks that give citizens a level of active control over their data and the right to know what is being done with it.

As an example, the Federal government has recently issued Australia’s Cyber Security Strategy 2020, that aims to “invest $1.67 billion to build new cyber security and law enforcement capabilities, assist industry to protect themselves and raise the community’s understanding of how to be secure online.”

The Federal government is also looking to enhance personal data privacy and security through the Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Act 2021. Passed in early 2021, the Act sets minimum standards for how digital platforms make available interactions of user data of the platform service with news content to that registered news organisation.

As more organisations embrace these good practices in ethical design and governance, governments will be better equipped to mitigate risks, safeguard against harmful outcomes and build the trust that is needed to use data to deliver better public policy outcomes.

Related article

3. Public participation and engagement

In the future, top-down models of governance will no longer be seen as legitimate or efficient. Many citizens expect decision-making to be shared, open and participatory.

Governments have an opportunity to engage citizens on the issues they care about. New digital e-participation tools, such as social media, mobile apps and online digital platforms, allow governments to collect input from citizens on a large scale, providing insights to enrich policy development and decision-making.

Governments can also ensure people are not just consulted but empowered to shape the decisions that affect them. Many are experimenting with different models for engagement to identify, debate and decide on a wide range of topics. For example, deliberative citizens’ juries have been used in Australia, as well as in Ireland and other countries, to co-create solutions to complex social and economic challenges. In South Australia, citizen juries have been tasked with unearthing solutions to nuclear waste storage, road safety and improving Adelaide’s nightlife.

More extensive solutions through empowered decision-making have also been used. The initial design of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in Australia, for example, was predicated on the Federal Government co-creating their policy response to supporting people with disabilities with those that were receiving the support. The NDIS gave individuals the ability to devise their own plan and have some agency over how their budget for support would be allocated across services.

We also see growing interest in participatory budgeting initiatives that allow citizens to decide how to allocate public budgets. More than 180 policy labs, including the University of Melbourne Policy Hub, have been set up globally to incubate ideas and provide a testbed for policies in areas such as education, health and justice. Similarly, government-organised hackathons have proved an effective way to engage people in finding fresh solutions to the economic, social and technological challenges posed by COVID-19.

Most governments and public authorities across the world are launching Open Data initiatives and setting up data exchange platforms that put power back in the hands of citizens and consumers. The focus is on making data widely available to third parties, including citizens, to help develop new solutions to complex problems while improving transparency and accountability, and creating a strong digital economy for all.

Related article

Why governments need to know their Connected Citizens

Governments around the world aspire to have strong and robust digital economies. While the private sector may have set the bar for digital transformation and consumer expectations, governments are now starting to provide leadership and accelerate their programs and implementations.

Governments are also leaning in to address their role. Are they just the legislator and regulator, expecting others to be responsible for this digital transformation? Or are they facilitators of and participants in a digital economy? The pendulum is swinging towards this latter role, with the pandemic accelerating this shift.

Governments also need to provide innovation and technology leadership so the ecosystem better serves Connected Citizens whose aspirations to be served on their own terms grow with each generation.

Advances in data and technology afford governments a unique opportunity to better serve their citizens. But, as with any transformative opportunity, there is an inherent risk: that an ambition to digitise and transform as much and as quickly as possible sometimes results in a one-size-fits all approach that actually fits only a few, leaving many further disconnected from government, physically and attitudinally.

Governments must grasp this moment to transform and lead by showing ambition and implementing a coherent Digital Transformation program for a digital economy. Studying the seven Connected Citizens personas will help governments plan digital service delivery mechanisms that cater for each citizen's needs.

In doing so, governments can become more effective and more efficient, while addressing digital exclusion to help reduce social inequality. At the same time, they will help build a more equitable and better working world for every citizen.

Meet the Connected Citizen personas

Summary

Citizens increasingly demand government services that are as accessible and personalised as those that they enjoy from private sector providers. They also want to be more engaged in how those services are designed and delivered. This creates an opportunity to strengthen the relationship between governments and the people they serve, growing trust to the levels needed for effective government.

But governments must also avoid leaving behind groups that are challenged by the shift to digital. Innovative policy design, accelerated digitisation, better use of data and participatory engagement with citizens will be important components of all governments’ responses to rising expectations and citizens’ confidence in data privacy and consent.