Energy transition is inevitable, as is the peak of oil demand. But when and how? There are numerous complicating factors at play, not the least of which is human nature.

Electric vehicle penetration

Transportation accounts for about 15% of carbon dioxide emissions. Transition from gasoline-powered cars to EVs won’t solve the climate change problem, but it will make a significant impact. Our research shows that the technology necessary to make EVs commercially competitive is either with us or close at hand. Technology though isn’t everything.

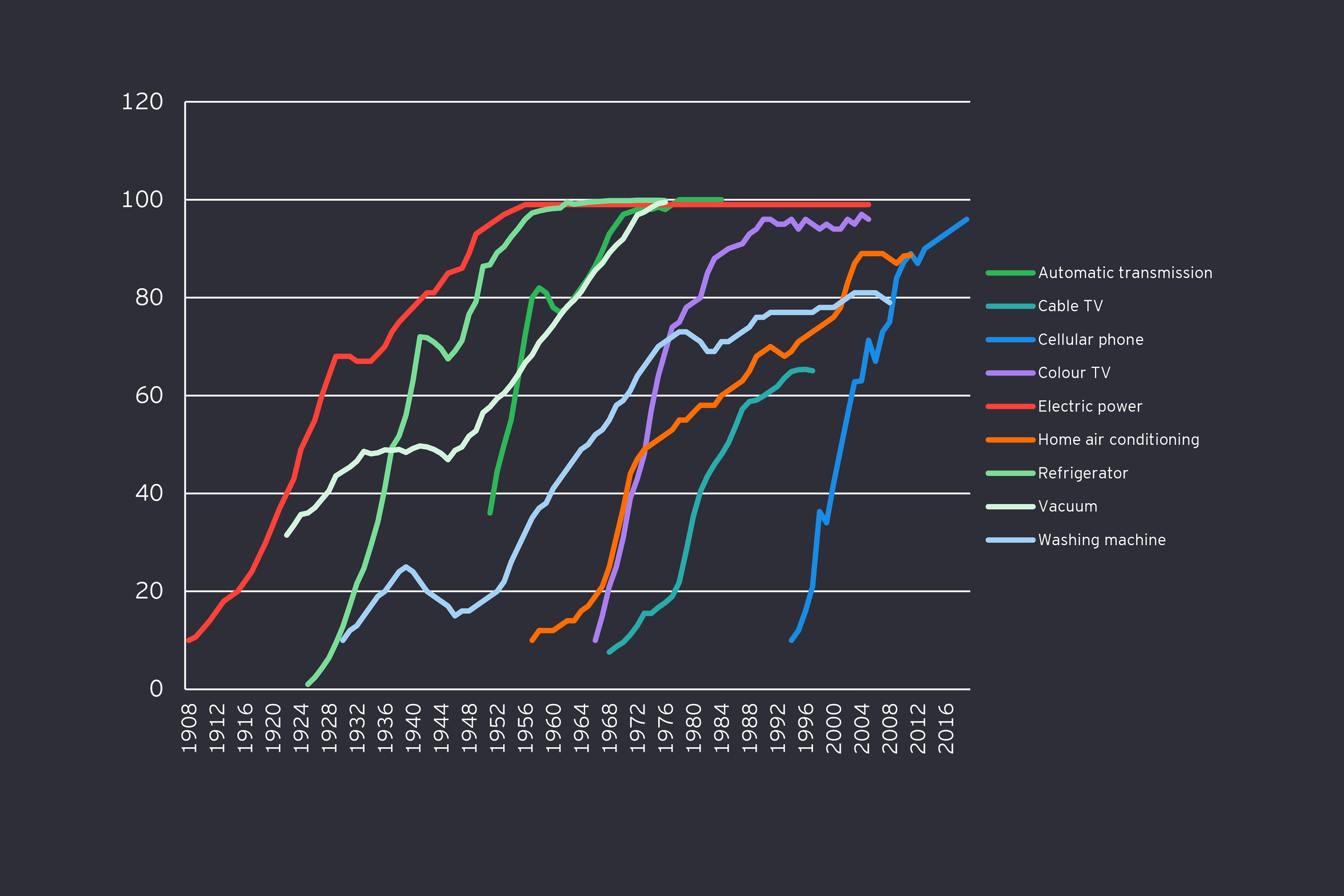

The consumer adoption graphic shows us the percentage of consumers who adopted new technologies in the years following their introduction. The variation is striking.

After electricity was introduced, almost 50 years elapsed before it was fully ingrained in our way of life. But the smartphone was on the market less than five years when about 75 percent of the US population had one.

There is no doubt that the Information Age has made it easier for consumers to get comfortable with new things. The word gets out quickly when something works well, and people respond by joining the ranks of adopters. The color television and the mobile phone are fitting analogies for EVs. In both cases, they provided the same service as something that people already owned (black-and-white TVs and landline phones), but better. In both cases, it took about 20 years for the new to displace the old.

Both innovations were successful. They were clear improvements and, in the long run, about as cheap or cheaper. When it comes to EVs, we’re optimistic, but there is still uncertainty. We see three big question marks:

- When will EVs be fully introduced to the mass market? The cheapest models are still considerably more expensive than ICE-powered cars and aren’t available in volume.

- How quickly will the cost and performance advance, and how quickly will consumers become aware, and convinced, of the cost and performance advantages? Interestingly, if the technology is perceived to be advancing, many consumers may defer adoption and push the curve out. We also don’t know how oil and gasoline prices will unfold over time. Drilling and completion technology is constantly improving. Costs are falling, and competition may bring lower liquid fuel prices.

- How quickly will the infrastructure required to charge EVs be fully scoped out and financed?

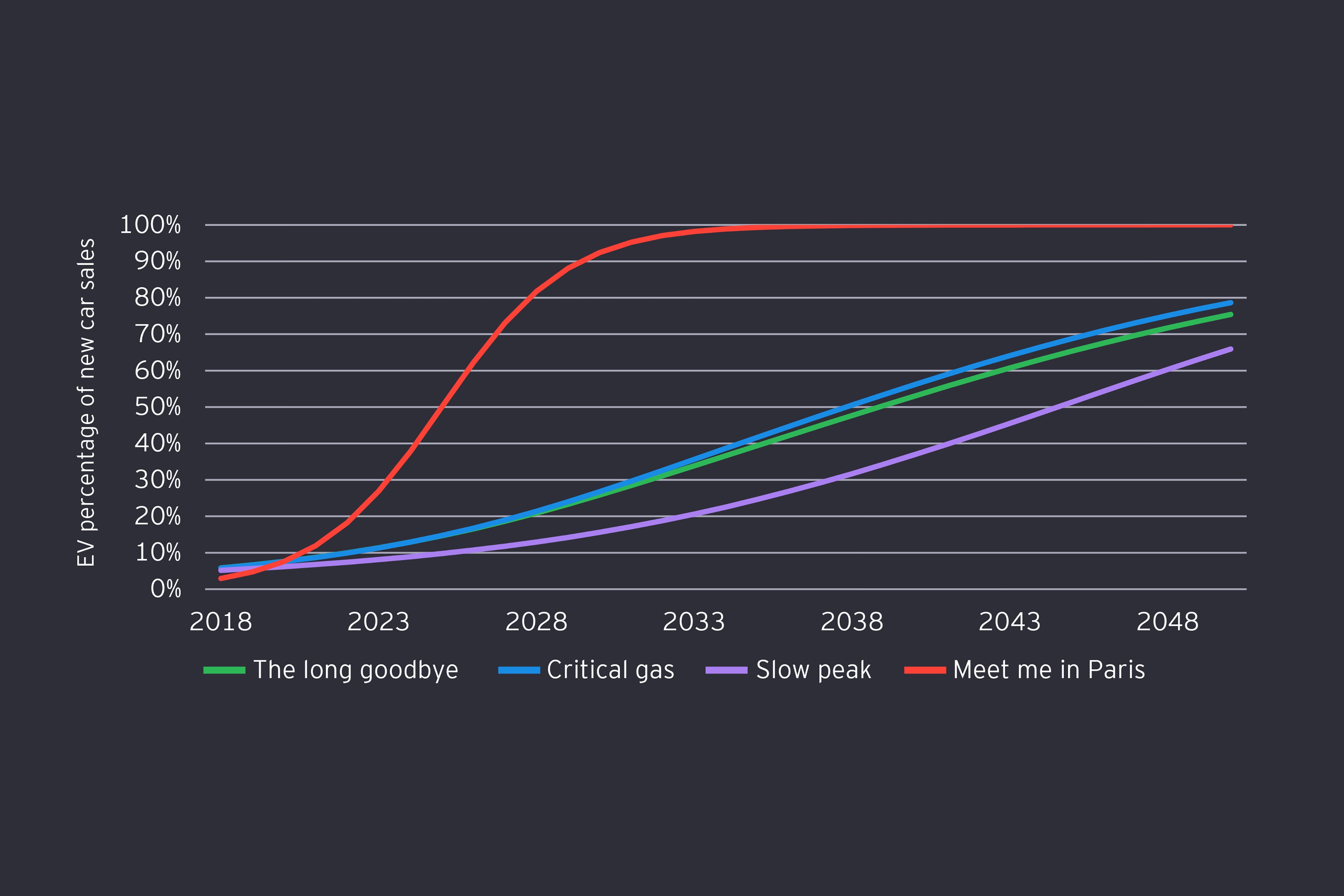

EV Adoption by scenario

Time will tell how quickly consumers believe in the benefits of EVs. The EV market share approximately doubled between 2017 and 2018 and will achieve 22% market share if there’s sustained 12% annual share growth between now and 2035. However, EV market share will barely advance between 2018 and 2019 in North America and China because subsidies have shrunk.

We therefore think that this scenario is pessimistic but plausible.

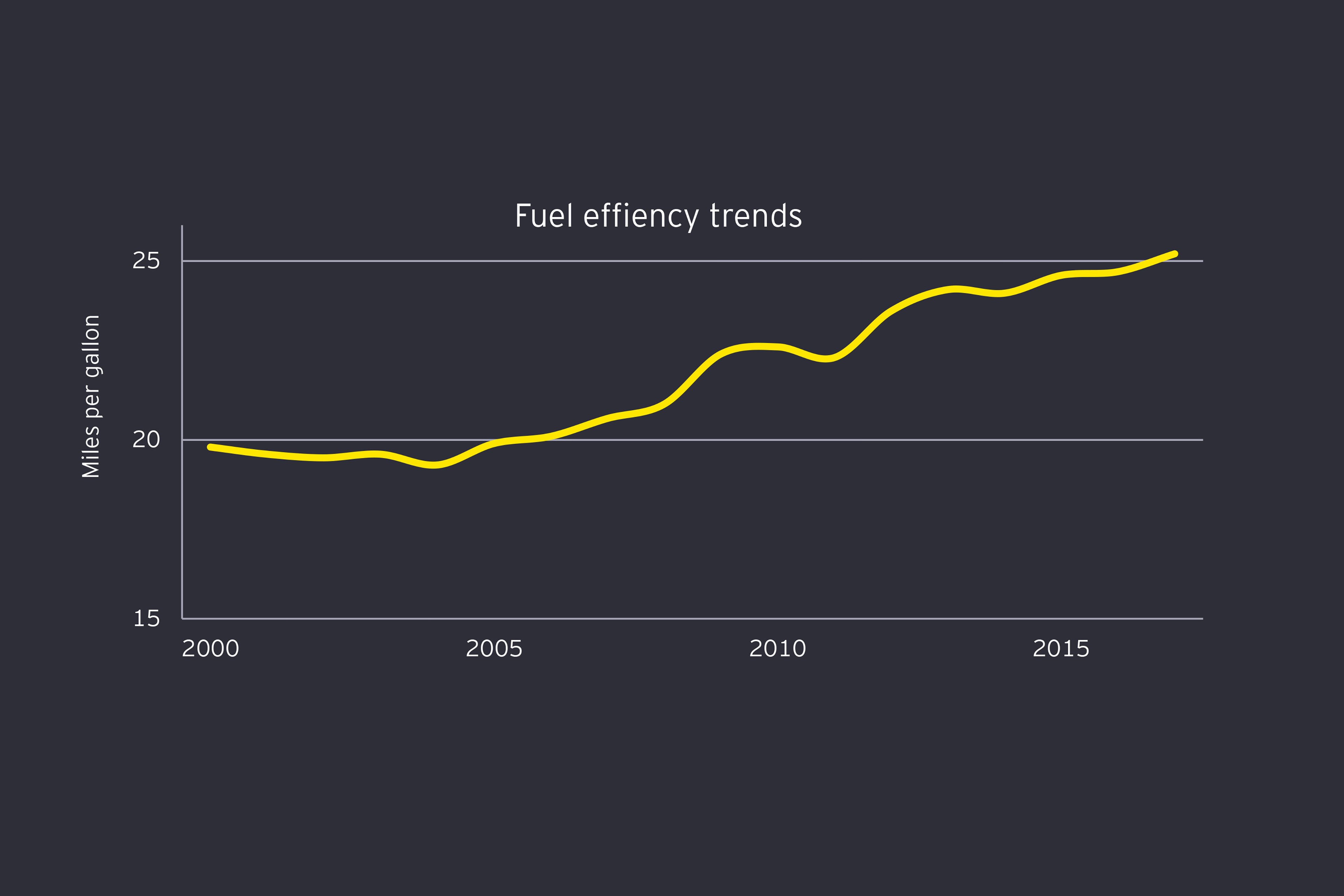

ICE efficiency improvement

The efficiency of automobiles has improved at a rate of about 1.5% per year since 2000. Several variables affect this, but it’s mostly about the price of fuel, consumer vehicle preference (car vs. truck or SUV), and government efficiency standards. Auto manufacturers can bring many features to the market that make cars more fuel efficient. Cost is the main obstacle, but one that’s easy to overcome if gasoline is expensive, consumers are more energy conscious and government requirements are stiffened. We also expect competition from EVs to be an important driving force for efficiency.

Slow Peak assumes that efficiency growth slows. Upstream costs fall, making oil (all other things constant) more plentiful and cheaper, giving consumers less incentive to buy fuel-efficient vehicles. Government commitment to increased efficiency fades, and standards are relaxed. Auto manufacturers respond by offering less-efficient vehicles. The net result is a 0.5% annual improvement in ICE efficiency, in contrast with the other three scenarios: 1.0% for the Long Goodbye and Critical Gas scenarios and 2% for the Meet Me in Paris scenario.

The growth of developing economies

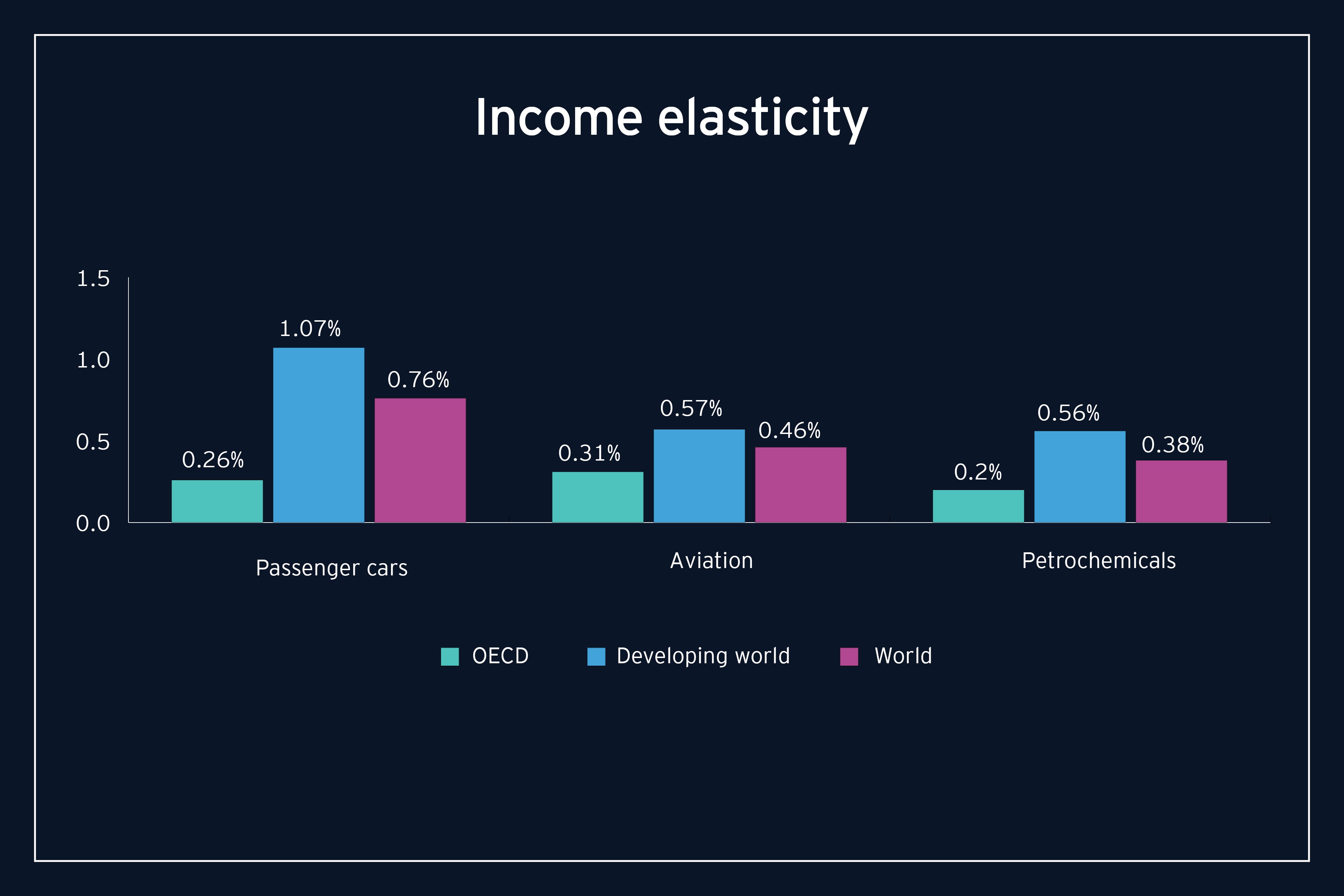

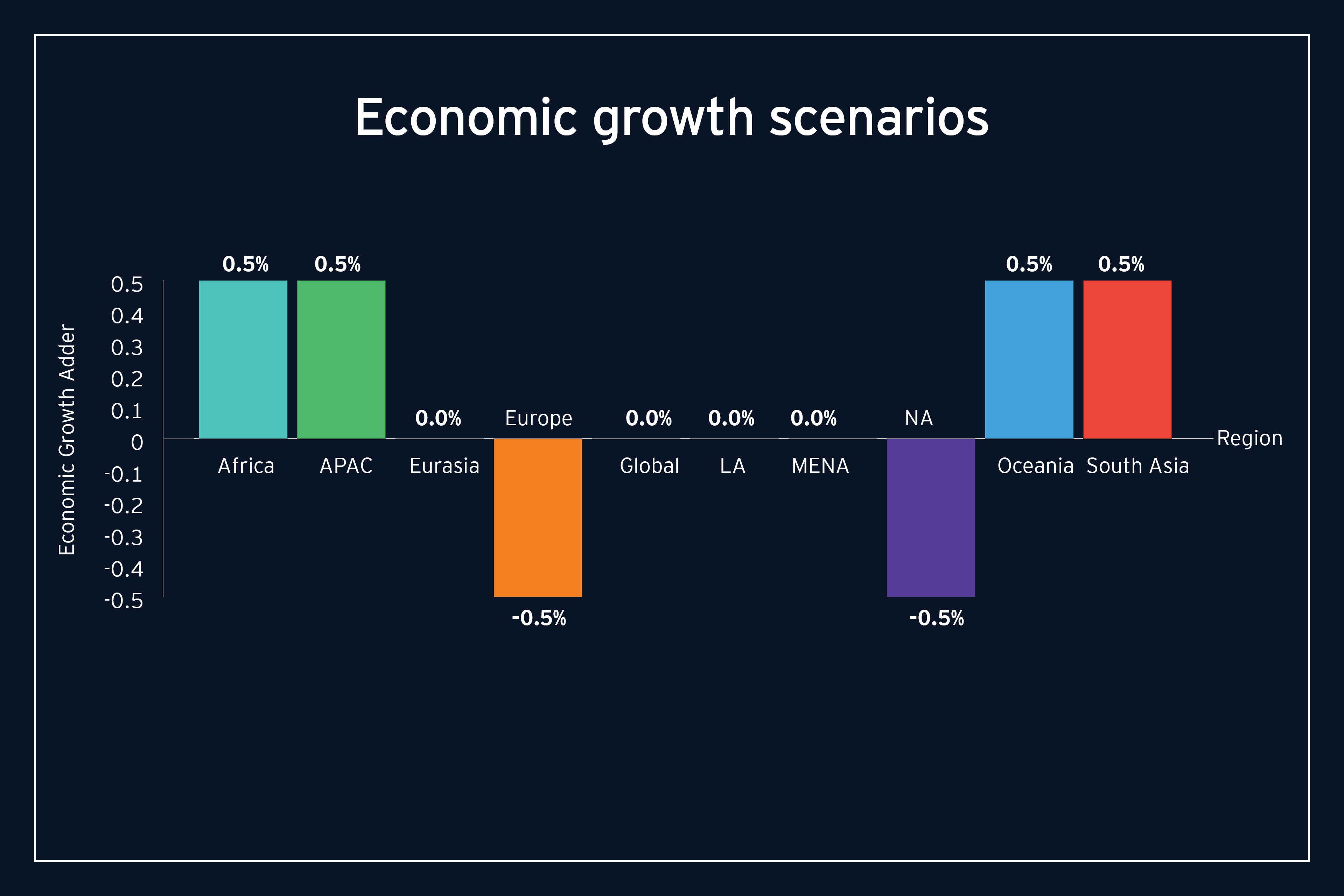

There’s more to oil demand than road transportation, and most observers agree that the strongest growth (perhaps the only growth) in petroleum demand will come from petrochemicals and aviation. For both segments, there are no immediate viable non-oil substitutes (although plastic recycling may be one soon), and both are strongly related to personal income. As developing countries advance, they will want to travel longer distances by air and to own more manufactured goods that use plastics. We model the growth of these sectors as a function of income, with the sensitivity varying from region to region. Consumption of almost everything energy-related (transportation, aviation and petrochemicals) is more responsive to changes in income when income is lower. The Slow Peak scenario reflects a shift in growth from the developed world to the developing world. Specifically, growth is assumed to be 0.5% higher in Africa, Asia, Oceania and South Asia and 0.5% lower in Europe and North America. That’s how you get to a Slow Peak.

By the numbers

When it comes to liquid fuels, the Slow Peak scenario is the mirror image of the Meet Me in Paris scenario.

| Meet Me in Paris | Slow Peak | |

| EV Market penetration - 2035 | 100% | 22% |

| Increased ICE fuel efficiency | 2% | 0.5% |

In the Meet me in Paris scenario, economic growth is one percent higher, relative to The Long Goodbye, in developed countries and one percent lower in developing countries. Transportation energy demand growth slows (since developed countries are well up the consumption curve) and it occurs disproportionately in parts of the world that are better able to fund alternative energy. In the Meet Me in Paris scenario, peak oil occurs quickly.

In the Slow Peak scenario that trend is reversed. Energy demand grows faster as an emerging middle class in developing countries begins to satisfy their desire to be mobile and is concentrated in parts of the world where funding for energy alternatives may be scarce. Peak oil is deferred.

In the Meet Me in Paris scenario, peak oil demand occurs in 2022. In Slow Peak, it doesn’t occur until 2047. Both “bookends” are plausible in our view.

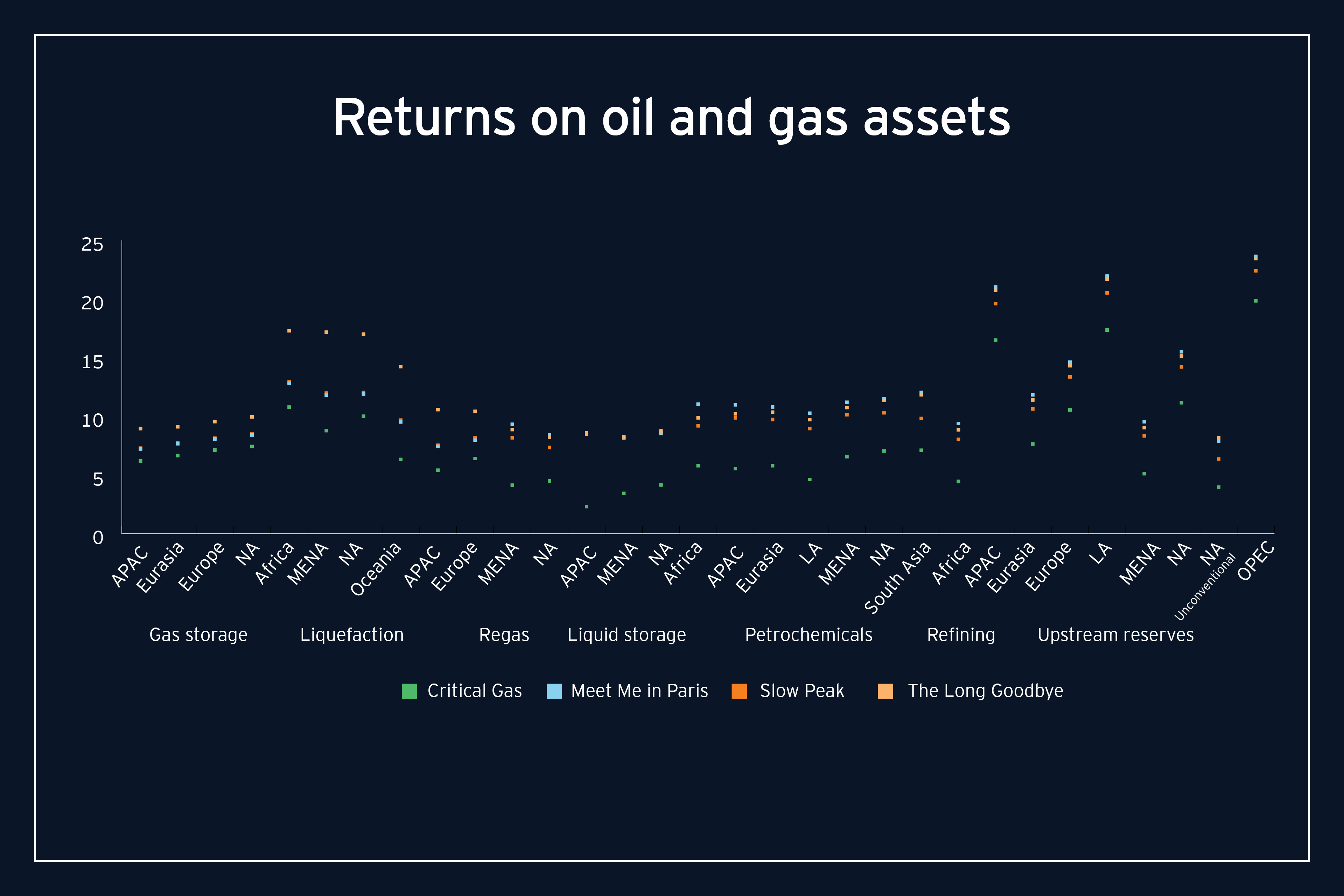

Returns hold steady

Oil demand and the demand for refined products and chemicals remain strong. The industry’s thirst for capital is sustained and consistent, and returns for oil-focused assets are big, relative to our other scenarios.

Habits are hard to change, particularly when they must change in a significant and sustained fashion in multiple countries at various stages of development. The Slow Peak scenario reflects that. Consumers have been using the same technology and the same infrastructure to get from here to there for generations. Persuading them to adopt new habits that are tuned into new technology and new infrastructure will take time. Perhaps a generation and perhaps much longer than what is envisioned by those who engineered and agreed to the Paris Agreement.

Energy transition is inevitable, as is the peak of oil demand. But when and how? There are numerous complicating factors at play, not the least of which is human nature. Companies managing their oil and gas business today must focus on all of them, as they try to determine the ways that people, capital and technology can be channeled to fuel the future.

Summary

In a Slow Peak world, continued upstream cost reductions muddy the competition between hydrocarbons and renewables. Transportation demand in developing countries surges and defaults to the incumbent technology (ICE), while consumer perceptions about EV performance slows electric vehicle adoption. Peak oil eventually happens, but not soon. Growing economies in developing countries drive demand for petrochemicals, energy intense industrial usage and aviation.