Chapter 1

Understanding public responses to the crises

Behavioral economics sheds light on why people do not always act as predicted.

Behavioral economics — a subject we have covered regularly across several years of EY Megatrends reports — is a cross-disciplinary field applying insights from psychology to understand how people make decisions in realms such as finance and health care. What makes the subject fascinating is that it is often counterintuitive — revealing that we do not always act as common sense or economic self-interest would predict. However, by understanding the biases and heuristics underpinning our behaviors, we can design incentives and messaging that actually work.

These behavioral biases and heuristics are visible in the public’s response to the COVID-19 crisis. For instance, behavioral economists know people have a hard time accurately assessing very large numbers or very small probabilities — which is one reason lotteries are a booming business. This behavioral shortcoming was evident at the outset of the crisis, when many interpreted public messaging about the new disease’s mortality rates as evidence of it being relatively harmless. Similarly, the average person had a hard time appreciating the deceptive potential of exponential math, which could transform a trickle of initial caseloads into a devastating wave in a matter of weeks.

Prior experience applying behavioral economics provides insight into resistance against social distancing and other behaviors. Why do many of us fail to exercise regularly? Blame “hyperbolic time discounting,” which leads us to underweight the future cost of current behavior — the same principle many apply when discounting the long-term health consequences of COVID-19. Why do we jettison our new year’s resolution to eat more healthily and surrender to temptation when confronted with an extra scoop of ice cream? That’s because the ice cream hits us in what behavioral economists call a “hot state,” while our resolution was made in the more rational “cold state.” When it comes to the pandemic, social-distancing guidelines are similarly at risk of being abandoned when people are presented with a fun social gathering.

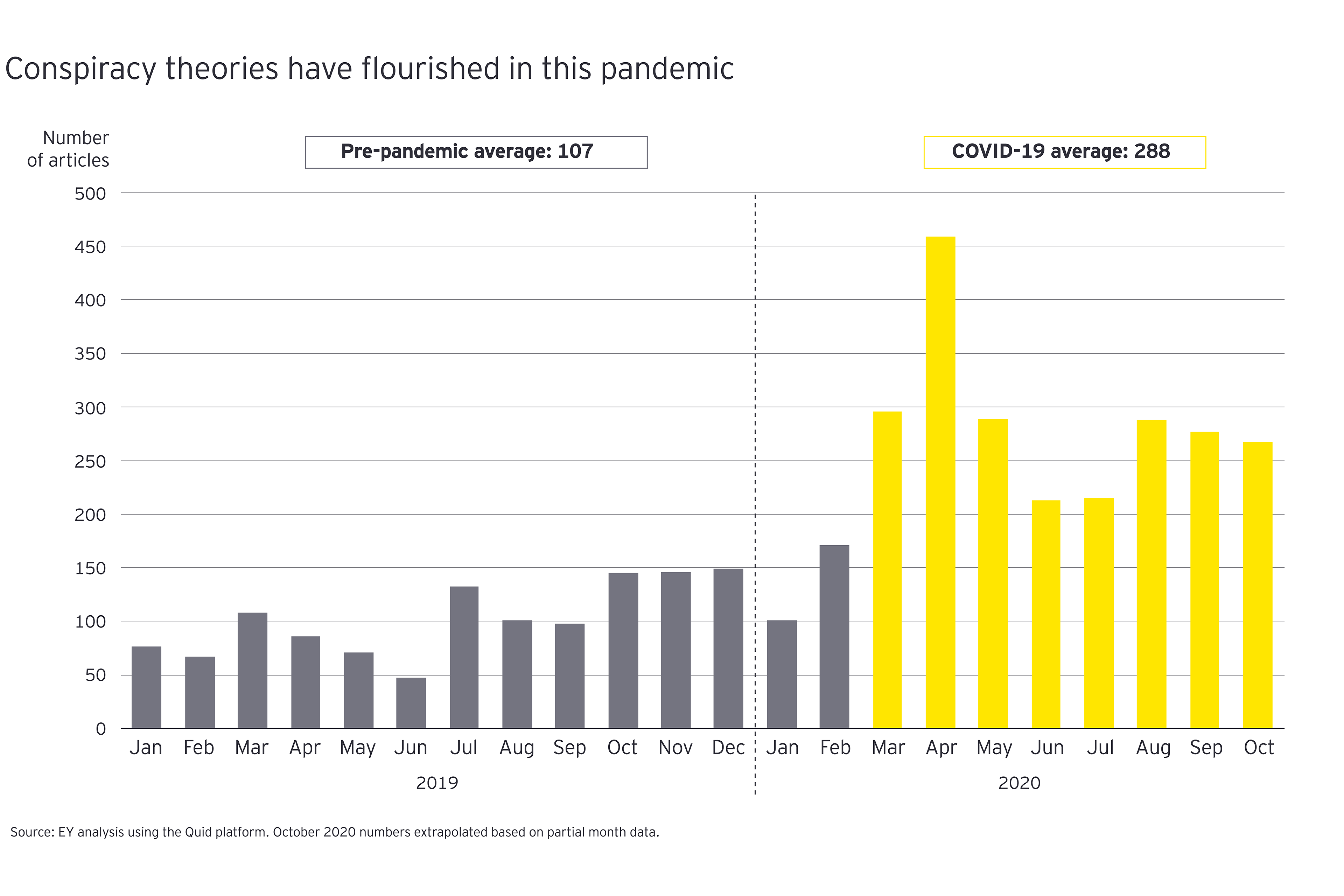

At the same time, the novel coronavirus has fueled an “infodemic” — an overwhelming onslaught of information and disinformation. The response to this has been disheartening. Conspiracy theories have gained traction. The number of news stories about conspiracy theories increased by almost 170%, from an average of 107 stories per month before the crisis to an average of 288 during the pandemic, according to EY analysis using the Quid database. Disinformation about simple acts, such as mask wearing and social distancing, has fueled resistance in some locations, often along political lines. The anti-vaccination movement, already ascendant before the pandemic, has gained more adherents as conspiracy theories and political interference have fueled distrust.

Since March 2020, the average number of articles mentioning conspiracy theories has more than doubled.

Insights from behavioral economics and psychology also help explain these trends. The work of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, for instance, shows how we are hard-wired by evolution to be tribal. Haidt argues that our beliefs are shaped primarily by intuition and tribal identity rather than data and logical reasoning. Meanwhile, cognitive neuroscientist and EYQ Fellow Tali Sharot posits people tend to trust in-group information while being distrustful of information from elsewhere.

“We tend to distrust institutions or people that we perceive as different from us in some way — and political affiliation is one of those ways,” says Sharot. “For instance, we conducted a study in which we found that people strongly distrust information from those who do not share their political views, even if the information being shared has absolutely nothing to do with politics, such as — in our study — geometric shapes.”

Chapter 2

Applying behavioral economics to the challenges ahead

Physical and technological changes only go so far.

Nine months in, we are approaching a critical point in this pandemic. Over the past couple of months, we have seen considerable experimentation with the reopening of schools. Now, companies are beginning to reopen workplaces in measured and limited ways. Meanwhile, it is becoming increasingly evident the pandemic will not be over any time soon, as we collectively gird for an upsurge in cases with the onset of colder weather in the northern hemisphere.

What challenges will this next phase of the pandemic bring and how can employers and policymakers use behavioral economics to tackle them?

Managing the safe return to work will require a “two-geared” approach: managing the transition to safe reopening in gear one, and transforming the workplace for the future of work in gear two.

“The transition to safe reopening includes numerous health, physical and technological changes,” says Liz Fealy, EY’s Global PAS Workforce Advisory Leader. “Employers are reimagining and redesigning the physical workspace — everything from rethinking open office layouts to adding health self-certification and testing as well as sanitation stations and spacing workstations further apart.”

As Fealy points out, companies are also deploying technology at speed to enable touchless interfaces, and reimagining remote working: “Companies are really rethinking the purpose of the office as a place to collaborate, connect and network as opposed to a place to come to work.”

But physical and technological changes can only go so far. As we have already seen, behavior is at the root of the pandemic and any successful response to it. How can we learn from behavioral economics to motivate and sustain the right behaviors in the workplace?

This is a critical challenge, particularly at this point in the pandemic. Behavioral economists have been warning about the danger of a phenomenon that is now becoming increasingly apparent: behavioral fatigue. Nine months into the crisis, many of us are growing tired of the need for constant vigilance and starting to let down our guard. Psychologists and neuroscientists have good explanations for why this happens but, without delving into the inner workings of the amygdala and the hippocampus, let’s just say that this is a common phenomenon. It’s a real challenge, for instance, for baggage screeners at airports, who have to ensure that the exhausting and mind-numbing task of screening countless numbers of bags does not desensitize them to the point where they miss a real weapon when it shows up. In this pandemic, we are all our own baggage screeners and the consequences of a slip up can be every bit as lethal.

It is therefore increasingly critical to not just motivate good behaviors but to sustain them. What can employers do to address this challenge, as well as the other behavioral challenges identified earlier in this article?

Related article

Chapter 3

Three actions companies can take to sustain good behaviors

Trust, encouragement and default settings are crucial.

1. Use trust to combat the infodemic

We are living in an era of declining trust. Growing polarization and shrinking trust in institutions have provided fertile ground for the infodemic of disinformation. One noteworthy finding in Edelman’s 2019 Trust Barometer was that, against this backdrop of declining trust, the single most trusted institution is “my employer.” That’s good news for companies and their leaders, who now have the opportunity to both fill a critical gap in society and enable a safe return to the workplace by providing reliable, science-based information and guidance. Employers could become the one trusted source of information that employees across the political spectrum are likely to believe.

Trust is a scarce commodity. You have it. Use it wisely.

2. Utilize social norms to encourage good behavior

Behavioral economist Dan Ariely has written extensively about the distinction between market norms and social norms. Companies and their employees typically operate in the domain of market norms, which are transactional and motivated by financial return. But social norms, which typically dominate our interactions with friends and families, can be far more motivating when deployed in the workplace — which is why volunteer-driven Wikipedia and Linux continue to flourish and trounce better-funded rivals with large armies of full-time employees.

Social norms have played a significant role in tackling the pandemic since its onset. When the guidance to wear face masks was first adopted, for instance, public health messaging frequently emphasized that one wears a mask to protect others more than one does to protect oneself. Now, as behavioral fatigue sets in and case numbers are poised to rebound, employers would do well to remind workers of the social norms underpinning their behaviors. In doing so, they would also reap an ancillary benefit, by fostering a greater sense of community in the workplace.

We are all in this together. How can you do well by doing good?

3. Use default settings and choice architecture to combat behavioral fatigue

A textbook example of the power of behavioral economics is with respect to organ donation. In countries where organ donation is an “opt out” (people are automatically enrolled as organ donors unless they explicitly state otherwise), participation rates are dramatically higher than in countries where the decision is an “opt in” (people are not enrolled unless they explicitly choose to become organ donors). Most people, it turns out, just go with the default setting.

The behavioral economist Richard Thaler, who popularized the term “nudge,” has written extensively about the power of choice architecture — designing the number of choices, the sequence in which they are presented, the use of a default setting, etc. — in influencing behaviors.

These insights are particularly relevant as employers reopen workplaces amid a backdrop of behavioral fatigue. The use of choice architecture and, in particular, default settings, can free up workers from having to make decisions and can help combat behavioral fatigue. This could include everything from mandatory testing upon arrival to physical cues for social distancing, similar to the markers that have become ubiquitous in retail settings, and the placement of hand sanitizer dispensers next to doorknobs.

How can you free your workers from behavioral fatigue while creating a safer workplace?

Summary

As we move into the next phase of this pandemic, we will need good behavior more than ever. Meanwhile, behavioral fatigue is on the rise, compounding the challenge for employers as they look to safely reopen. Simple behavioral techniques — from establishing default options to channeling social norms — can go a long way toward keeping workers safe and businesses humming.