Chapter 1

Reform social protection and care systems

Ways to extend coverage to more elderly and vulnerable people.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the urgency of social protection reform into stark relief. It has exacerbated many existing social problems and has disproportionately affected some of the more vulnerable segments of society. In the years ahead, governments will be called upon to support larger numbers of vulnerable people, and to do it better. But the vast majority of the world — 71% or 5.2 billion people — are inadequately or not at all covered by social-protection schemes.

There is cause for optimism, however. The current crisis could serve as the catalyst for a new social contract, just as the Second World War led to a significant expansion of the welfare state in many countries. Indeed, people may now be receptive to radical reform, having felt a new sense of connection with and responsibility for their fellow citizens during the pandemic.

Even before COVID-19, many commentators were arguing for a universal basic income (UBI), minimum income guarantee or other similar schemes that offer regular and unconditional transfers of money to offer a basic means to live. The appeal of such schemes has risen as millions find themselves unemployed, furloughed or struggling with loss of incomes and an uncertain future. These programs could continue over the long term, to offer support and protection to the self-employed, those on zero-hours contracts, or people doing unpaid work, such as caring for relatives. In Spain, the Minister for Economic Affairs, Nadia Calvino, has already announced the country’s intention to make UBI a permanent “structural instrument” once the crisis is over.

Related article

A global shortage of around 13.6 million long-term care workers, combined with the lack of universal health care coverage, means that close to half of the population aged 65 and above has unmet care needs.

More broadly, the crisis may present the opportunity to create more comprehensive, efficient and permanent social protection systems. Governments can reduce the future financial burden of social security benefits by projecting the needs of the population and taking preventative action before crises occur. One vision for an inclusive recovery is New Zealand’s post-pandemic “Wellbeing Budget,” which prioritizes not just financial health, but also natural resources, people and communities, through investment in mental health, indigenous people, poverty reduction, education and skills development. New-generation protection systems will need to be flexible enough to support individuals pursuing nontraditional life and career paths, including intermittent, part-time and informal working, and frequent career changes.

The pandemic has also highlighted some very real issues for elderly populations around the world. Beyond the immediate health impact, it has put older people at a greater risk of poverty, discrimination and isolation. But a global shortage of around 13.6 million long-term care workers, combined with the lack of universal health care coverage,1 means that close to half of the population aged 65 and above has unmet care needs. Governments will increasingly look to change how they support, care for and value older people through reforms to their aged care systems.

Chapter 2

Embed digital public service delivery models

Turning short-term fixes into strategic advances.

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen more governments turn to new technologies and delivery models to help them tackle multiple dimensions of the crisis. The greater adoption of digital channels across social services, health, education, justice and taxation during the pandemic offers the potential for many long-term benefits in terms of quality and accessibility of services, as well as efficiency gains.

For example, new digital platforms have helped citizens better understand and navigate social services entitlements, check their eligibility, and submit and track applications. And, we have seen an upsurge in digital health solutions such as remote consultations, telehealth platforms and artificial intelligence (AI)-powered assessment apps, which many users have found convenient. The UK Government is looking to make all general practitioner consultations virtual on an ongoing basis, unless there is a strong clinical reason for a physical meeting.

During the crisis, social services agencies noted a decline in reports of concern about the most vulnerable children and families from the usual points of referral (such as schools and hospitals). This has heightened concerns for their welfare and led to fears of a surge in demand for services as we emerge from the crisis. In response, some agencies are putting greater emphasis on using data from a wide range of indicators to identify "at risk" individuals and families so they can take preventative action and prioritize resources effectively to meet future demand.

Some services will return to a "face-to-face" model once it is safe to do so. However, in many cases, a hybrid model is likely to emerge, blending new digital delivery mechanisms with the best of traditional, in-person services. For example, in the early days of the pandemic, students in many countries moved to the remote learning model within days. The temporary shift gave education providers a chance to think about the opportunities for ongoing student-centric and digital learning that can offer real benefits in terms of outcomes.

To ensure digital services are accessible to all, many governments are considering investing in (or regulating for) the creation of supporting infrastructure such as 5G and broadband. 5G will provide the connectivity that will transform the lives of billions of citizens, enabling working from home, improved mobility, telehealth and online education. In India, the Kerala Government has announced that it will provide extra 5G bandwidth across the state as more people work and study online due to COVID-19.

Related article

Chapter 3

Re-empower local communities

A new settlement between central and local government.

Whether through greater support for neighbors in need or simply through spending more time using local shops, parks and services, communities have come together strongly during the COVID-19 crisis. In Brazil, for example, citizen activists formed "crisis cabinets," creating tailored public information campaigns, and taking food and other essentials to those in need.2

It is this kind of community spirit that will help citizens rebuild their communities and social infrastructure, delivering grassroots solutions that fuel positive changes. This spirit can be captured and sustained by encouraging more participative governance and re-empowering local communities to take leading roles in social care, town planning and service provision.

To be most effective, community empowerment will require the support of government. Scotland’s Government, for example, is funding community-led regeneration through its empowering communities fund, which aims to support the most disadvantaged or fragile communities. This gives people more power to make decisions on spending in their local areas through participatory budgeting, and making it easier for communities to take over land and buildings in public ownership through asset transfers.

With the right leadership, support and incentives, this revival of the local could become permanent, bringing many benefits such as support networks for the vulnerable, revitalized local high streets, and thriving local services and amenities due to increased usage. All of this would, in turn, lead to greater local resilience to future crises.

Local governments, regions and municipalities – with responsibility for health care, social services and economic development – have been at the frontline of crisis management during the pandemic. And they will continue to play a vital role in building resilient communities, facilitating and enabling networks, and supporting infrastructure and business growth to the benefit of their locality. The crisis presents an opportunity for local governments to reset and reframe their relationships with the center, but inter-governmental coordination will be vital.

Chapter 4

Tackle inequality

Planning for a fairer economy and society.

The crisis has exposed long-standing, structural inequalities in society, such as life-expectancy gaps, poverty, food insecurity, unequal access to health and social services, racist and identity-based violence, and employment in low-wages and less secure jobs. Meanwhile, the world’s billionaires have a combined wealth that is more than 60% of the global population.3

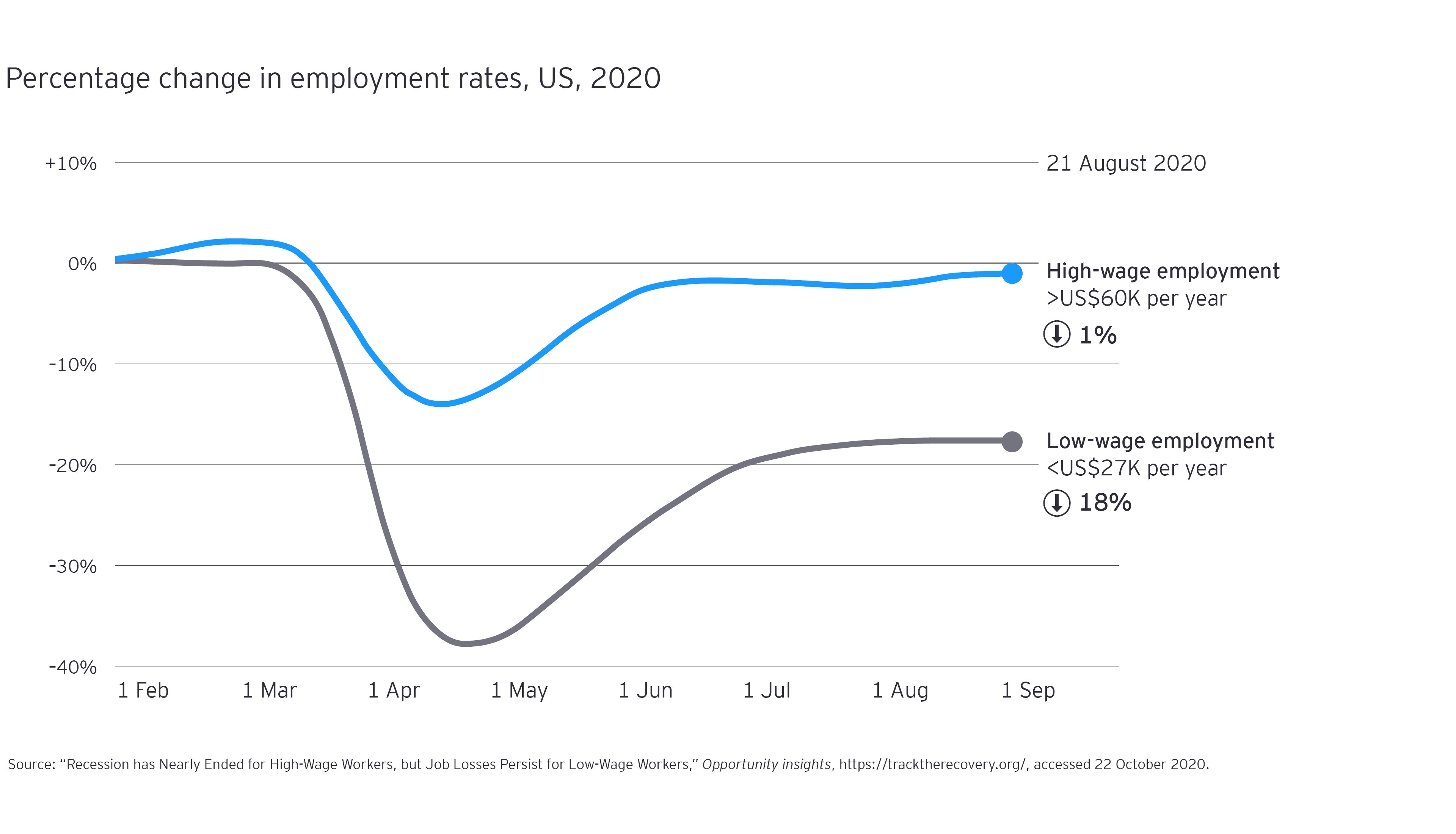

Evidence suggests that the recession will have a more prolonged impact on low-income workers. While employment rates have rebounded to pre-COVID-19 levels for high-wage workers in the US, for example, they remain significantly lower for low-wage workers.4

Evidence from previous crises shows that economic growth following crises can be associated with a reduction in inequality. This does not happen by accident, but through government action to invest differentially in education and skills for the future; to reshape social safety nets; to support the private sector in job creation; and to put in place a progressive tax system. With a rapid recovery looking unlikely before a vaccine for COVID-19 is deployed, and unemployment unlikely to drop back to pre-crisis levels, a specific action plan is required to address inequality.

One option is for governments to put a greater emphasis on active labor market policies (ALMPs) that can help unemployed and low-income workers find jobs or retrain. These ALMPs could include targeted tax incentives that encourage job creation and skills development in hardest-hit and future-oriented sectors. In the short term, ALMPs could also target stimulus relief linked to guarantees of job security and training.

This approach also requires the creation of more agile (and lifelong) education and retraining programs that adapt quickly to changing labor market needs, and help workers remain relevant and competitive. In India, for example, the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship has launched the Aatmanirbhar Skilled Employee Employer Mapping (ASEEM) portal to tackle the shortage of skilled workers. This AI-based platform will help people gain industry-relevant skills and find sustainable occupations post-COVID-19.

In addition, universal basic income (UBI) programs can also incorporate an education and training allowance for every citizen, providing a springboard for progression and personal development. This would not only provide economic security, but also allow workers to improve their employability and bargaining power with employers.

Related article

Summary

The economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis have exposed the weakness of social safety nets and the vulnerability of vital public services. Digital technologies can help build resilience in public services, but proactive policy choices are required if poorer, older and more vulnerable people are to be better protected against future shocks.