Ongoing geopolitical crisis and its potential economic impact

The WTO projected that the ongoing global turmoil may lower global GDP growth by 0.7-1.3% points to range between 3.1% and 3.7% in 2022. It also projected that global trade growth in 2022 could be cut almost in half, from 4.7% as forecasted earlier in October 2021 to 2.4% to 3%[2]. The UNCTAD, in its Trade and Development Report Update released in March 2022 reduced its global growth projection to an even lower level of 2.6% for 2022[3]. The World Bank in its ‘Europe and Central Asia Economic Update’, released on 10 April 2022, has assessed that in view of the ongoing global uncertainty, GDP in the Europe and Central Asia region is expected to contract by (-)4.1% in 2022. The IMF, in its April 2022 issue of the World Economic Outlook has projected global growth to decline from an estimated 6.1% in 2021 to 3.6% in 2022 and remain at the same level in 2023.

The 2022 and 2023 forecasts have been revised down by 0.8 and 0.2% points from their corresponding estimates in January 2022 owing to the ongoing geopolitical tensions. Maximum downward revisions in growth prospects have been made for the Euro area followed by the UK, apart from Russia and Ukraine. India’s FY23 growth projection has been lowered by 0.8% points to 8.2% reflecting weaker domestic demand as higher oil price is expected to weigh on private consumption and investment, and a drag from lower net exports. The FY24 growth forecast has also been marginally revised down to 6.9%. Despite these revisions, India is projected to lead global growth throughout IMF’s forecast period from FY23 to FY28.

CPI inflation in the US increased to 8.5% in March 2022, its highest since December 1981, led by an increase in prices of gas, shelter and food[4]. According to available information[5], the US Fed has signalled more aggressive rate hikes in the upcoming months. The pressure on US interest rate would eventually call for the RBI also to revise domestic interest rates upwards.

The RBI, in its first monetary policy review of FY23 held on 8 April 2022, retained the policy rate at 4%. With this, the repo rate remained unchanged since May 2020. The RBI has instituted a new facility called Standing Deposit Facility (SDF) with its rate to be placed 25 basis points below the policy rate, at 3.75%. The Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF) corridor has been restored to 50 basis points, ranging from 3.75% to 4.25%. The former is the SDF rate, and the latter is the Marginal Standing Facility rate. The RBI’s policy stance continues to be accommodative. However, recognizing that there is a liquidity overhang amounting to INR8.5 lakh crore in the system, the RBI indicated that there would be a calibrated withdrawal of liquidity over a multi-year timeframe to ensure that inflation remains within the target going forward, while supporting growth. The RBI revised its FY23 growth forecast downwards to 7.2% and its CPI inflation projection upwards to 5.7%.

The opposite movements in growth and inflation are likely to imply minimal changes in the nominal growth prospects. The FY23 nominal growth may be marginally revised upwards because the magnitude of increase in inflation by a margin of 1.2% points is higher than the reduction in the real growth forecast by a margin of 0.6% points. We expect that the implicit price deflator (IPD)-based inflation may be higher than the CPI inflation as the WPI inflation which has a higher weight in determining the IPD inflation, continues to be higher than the CPI inflation. During 4QFY22, CPI inflation averaged 6.3% while the WPI inflation averaged 13.8% implying an excess of 7.5% points over the CPI inflation. The expectation of a higher IPD-based inflation is also confirmed by the implied 4Q IPD-based inflation at 8.7%. In this quarter, the implied nominal GDP growth stood at 13.9%. Thus, there is a strong likelihood that nominal GDP growth may be close to 14% in FY23, which is well above the budget assumption of 11.1%. This in turn implies that there is scope for a higher than budgeted growth in Center’s gross tax revenues (GTR).

Considering a tax buoyancy of 1.1, growth in Center’s GTR may be estimated at slightly higher than 15%, which is higher than the budgeted growth at 9.6% that implied a buoyancy of less than 1. This would imply an improved fiscal space for supporting demand in the system. The RBI has also indicated an improvement in the manufacturing capacity utilization ratio to 72.4% in 3QFY22 from 68.3% in the previous quarter. If this trend continues and the government is able to support demand in the system through both, private and government final consumption expenditures, we may expect a revival of the investment cycle.

From crude oil to retail prices: role of central and state taxation

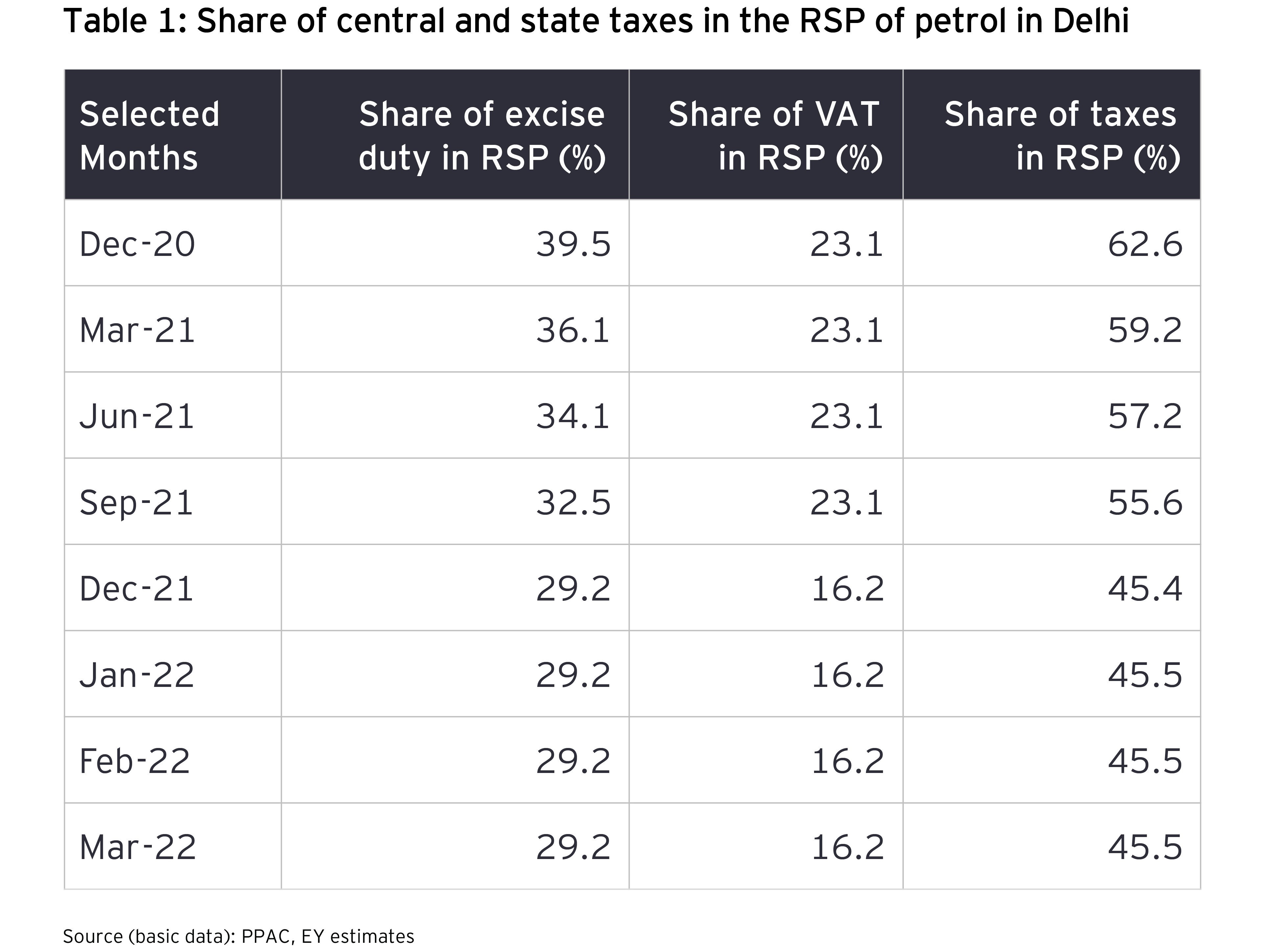

Table 1 shows that the central and state governments together accounted for 45.5% of retail price of petrol since December 2021. Both tiers of government had last reduced their tax share in November/December 2021. However, the policy option is still available for both central and state governments to give some more relief to the retail consumers and users by absorbing some of the global price pressures. It is further notable that the Center may have somewhat larger fiscal space for this purpose since the main channel of successive increases in central taxes on PoL products was through the route of non-sharable excise duty components. By 11 April 2022, petrol and diesel prices had been hiked 14 times in 21 days. Prices of both petrol and diesel have remained stable since then.