Chapter 1

Political risk is intensifying

Our research shows that political risk has increased dramatically in the past decade.

Political risk may emanate from transnational, national or civil society actors. Our research found political risk—across each of these levels—has increased dramatically in the past decade and, in particular, between 2016-2018. By many measures, it is at a post WWII high.

Transnational or geopolitical risks emerge when the interests of countries in defined policy arenas collide, or when the international system at large is undergoing a transformation. Trade and investment barriers have risen in the last 10 years and global conflicts are rising.1

Trade barriers

257%The number of discriminatory trade interventions implemented globally peaked in 2018, to 1,308, which is a 257% increase from 2009. (See article references: 2)

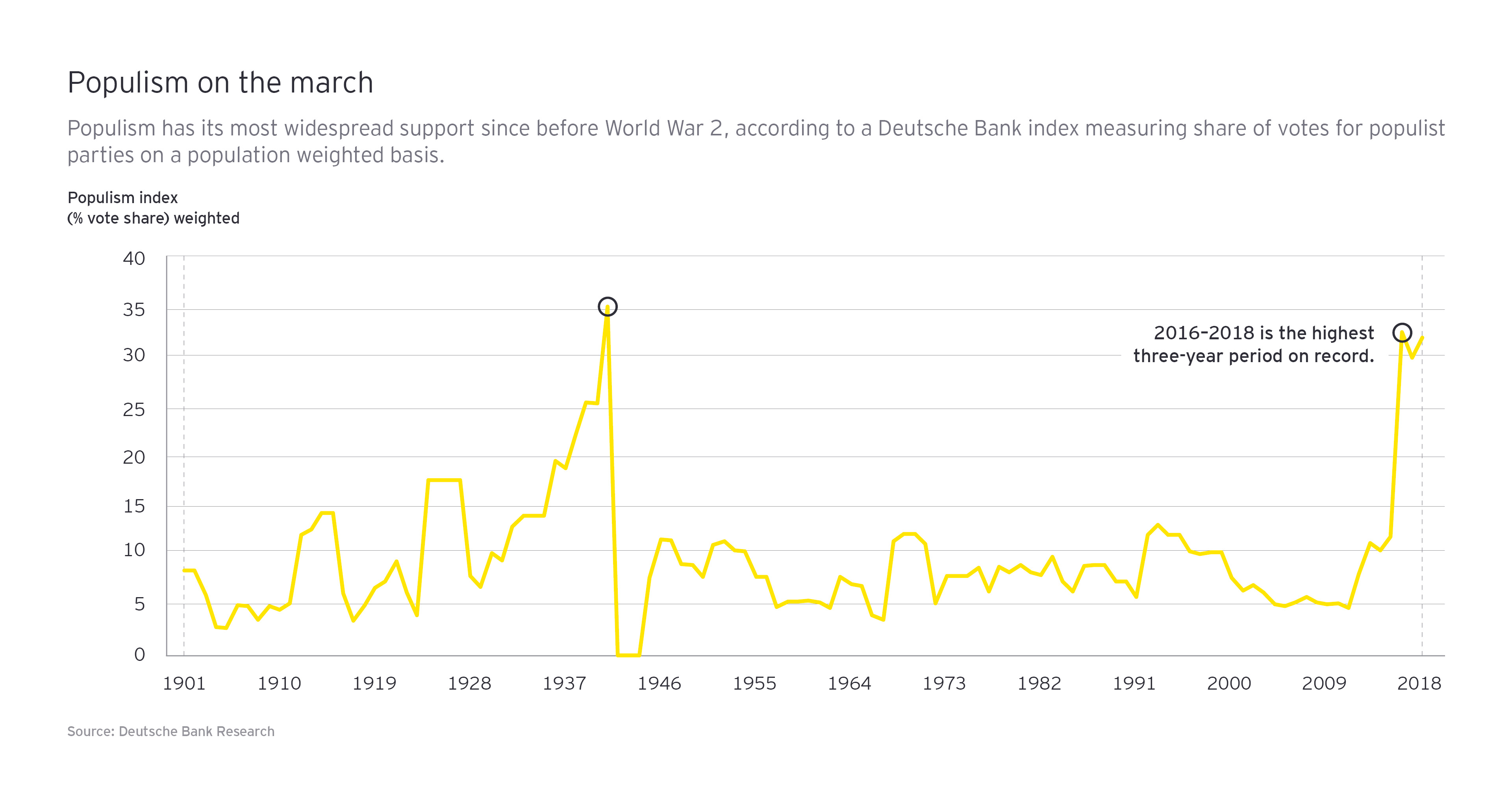

National or country risks emerge when question marks over the stability of government or institutions have economic consequences for the domestic market and its businesses (examples include policy shifts and corruption). At a national level, populist sentiment is growing, with recent research from Deutsche Bank showing support for populism at its highest since the time leading up to WWII.

Societal risks emerge when groups, from trade unions to consumer bodies, launch public activism such as boycotts or protests that have consequences for markets and companies operating globally. Sentiment analysis3 shows increasing negativity toward foreign businesses in the language of news articles, contributing to an environment of policy uncertainty.

Chapter 2

How political risk impacts corporate performance

Political risk affects organizations in myriad ways, from sales to reputation.

Political risk represents a web of interconnected issues that can materially impact organizations in myriad ways. Research demonstrates the significant impact it can have in a range of areas: sales, production and operations, research and development, security, finance, regulatory compliance, governance, and reputation.

Political risk: Significant cross-enterprise impact

Function: Sales

- Impact: Reduction in sales and revenues.

- Example: A series of cases that illustrate consumer preferences driven by nationalist sentiment, government policy (e.g., tariffs, quotas or regulation) leading to direct sales loss, and the actions of civil society targeting specific companies or products negatively impacting sales and revenue.

The Iraq War was found to negatively impact the sales of American products in Arab countries, with US sales growth lagging foreign competition’ by 21.2% in 2002–03.4

Function: Production and operations

- Impact: Disruption to FDI and M&A

- Example: A wide body of research that demonstrates the medium- to long-term negative impact of political risk on foreign direct investment and the magnitude of M&A. Diplomatic conflicts can increase the costs of doing business and M&As are more likely to complete in countries with stronger political institutions.

The outbreak of violent conflict near a subsidiary increases the likelihood of divestment by 52%.5

Function: Research and development

- Impact: Rising costs and intellectual property theft

- Example: Political risk increases R&D costs and can result in a loss of market share. In countries with high levels of political risk, companies have had intellectual capital forcibly transferred and potentially used in competing products.

Technologically leading firms were, in one study, eight times more sensitive to political risk than their technologically lagging counterparts.6

Function: Security

- Impact: FDI and market capitalization impact

- Example: We found evidence of how corporations facing political risk must contend with significant security threats to their people and physical equipment. The studies show that violence by non-state international actors aimed at global companies has been a growing and understudied material threat and serves as a deterrent to foreign direct investment.

Supply chain disruptions as a result of terrorist incidents were found to have a negative stock market reaction equal to 9% of market capitalization.7

Function: Finance

- Impact: Higher cost of capital

- Example: We found a range of studies that show how investors and creditors are wary of corporations that are facing significant political risk. They perceive these organization as riskier investments, which results in an increase in cost of capital. The research draws upon a wide range of financial information, from corporate bond yield spread to the likelihood of bailouts.

Increasing political risk from the 25th to the 75th percentile equates, approximately, to a 3% increase in the cost of capital.8

Function: Regulatory compliance

- Impact: Increased risk mitigation costs

- Example: Reliable legislation and regulation is essential for smoothly operating markets. The studies we found showed how companies are stepping up to the plate when there are no formal international treaties or agreements in place. They are arriving at voluntary agreements and self-regulating on topics like corporate social responsibility. The research also shows how companies look to shape regulatory outcomes by building networks of advocates.

An eleven-year study of public firms found that those with better reputations on societal (i.e., CSR) issues are given more standing in policymaking.9

Function: Governance

- Impact: Corporate governance challenges that reduce transparency and accountability

- Example: Research indicates that corporations facing political risk are associated with weak corporate governance (where a group of primary stakeholders gains at the expense of others). The research examines a range of governance areas to illustrate this link, from poor or suspect accounting data10 to politically motivated hiring.11

Function: Reputation

- Impact: Damage to the social license to operate

- Example: When they lose the trust of stakeholders, corporations can trigger political reactions and eventually lose their social license to operate. Key drivers of stakeholder conflict include negative environmental spillovers, displacement of homes, distrust, lack of political voice, inadequate compensation, corruption, criminal activity, inadequate planning and state bias in favor of industrial development.12

Individual characteristics that predict opposition to the activities of multinational companies include gender (women are more skeptical), youth, income, lower levels of skills and education, and nationalism.13

Cashflow downgrade

72%Without stakeholder support, investors have been found to discount future cashflows by as much as 72%. (See article references: 14)

Chapter 3

Companies need a more strategic approach

Companies lack integrated capabilities for managing the cross-enterprise impact of political risk.

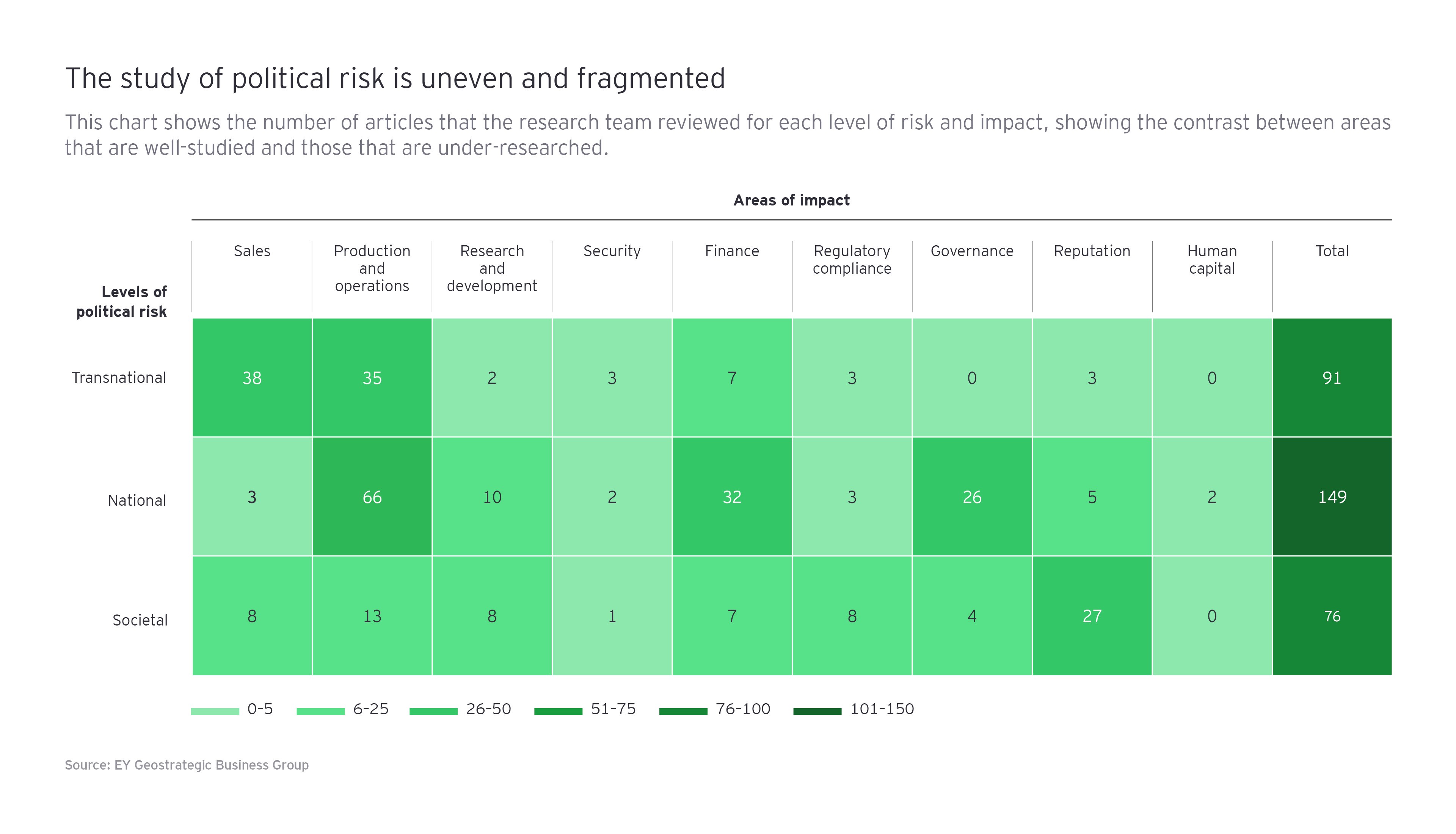

While political risk presents a significant cross-enterprise threat, many senior executives tell us they lack an integrated and systemic capability for sensing critical risks, leaving them struggling to mitigate threats or seize opportunities. A whole-company response is difficult because while we know political risk is driven by the same transnational, national and societal triggers, how they affect an organization varies. Companies need to manage a complex system of relationships but today have little guidance: the study of political risk is fragmented and some areas, such as the impact of national risks on sales, are under-studied (see “The study of political risk is uneven and fragmented”).

More holistic academic analysis of political risk would identify the best strategic responses for a given constellation of political risk drivers and impacts.

Fragmentation in the study of political risk is mirrored by the treatment of political risk in practice. While political risk has a multi-dimensional impact—affecting everything from how consumers behave (sales) to the management of supply chains (production and operations)—these issues are typically the focus of individual functional managers.

However, if the impact of political risk is considered organization-wide, its cumulative impact is much larger—as is the ability of the company to influence its frequency and magnitude. A negative impact on sales, for instance, may be altered through a strategic response in sourcing. Impact on regulation could be altered by additional domestic hiring. The threat of corruption could be mitigated by a different regulatory strategy.

It’s through such strategic management of political risk that companies can protect value and increase growth opportunities. But it requires new capabilities for CEOs, boards and senior leaders.

Chapter 4

Geostrategy

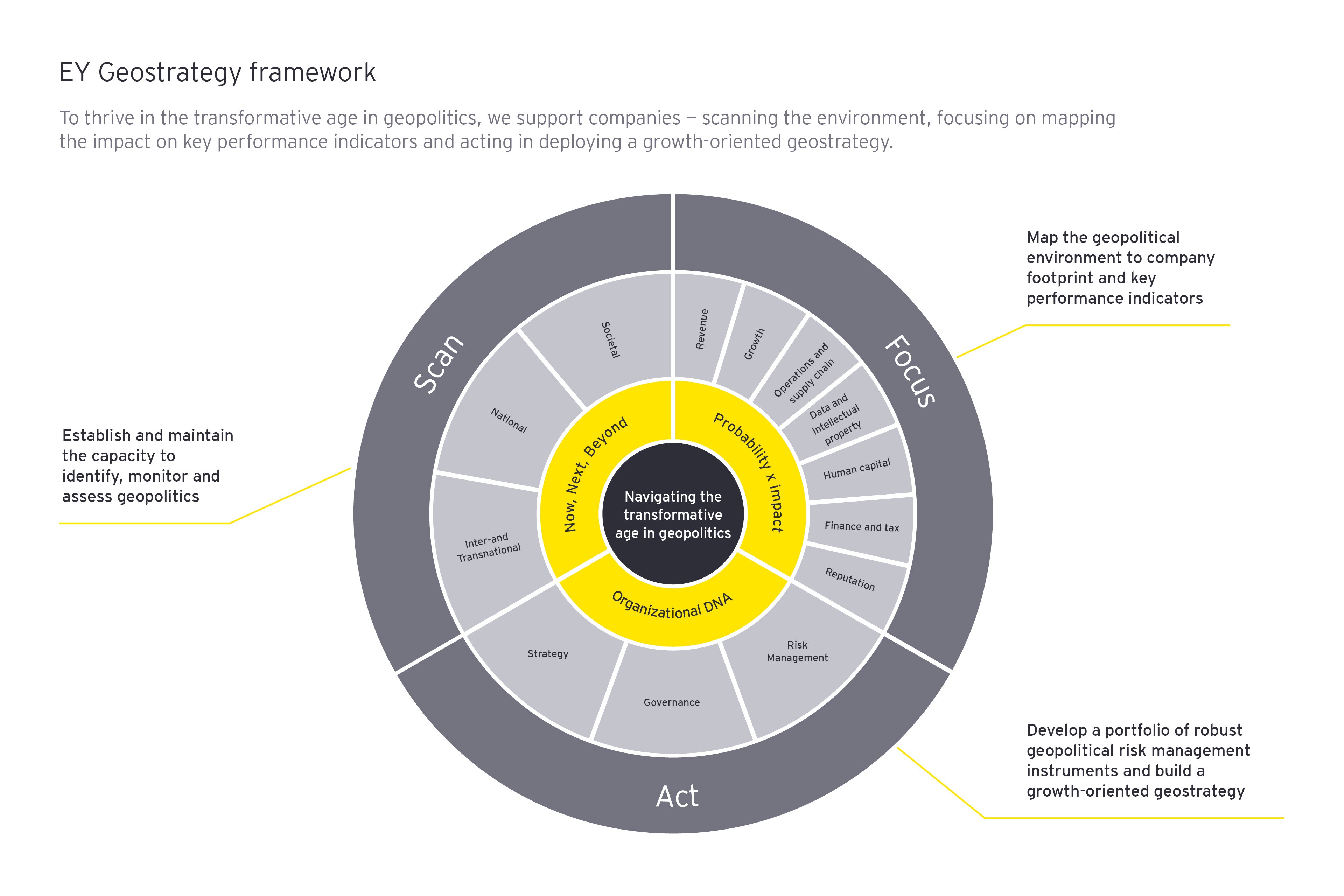

A robust geostrategy integrates political risk assessment into risk management, strategy and operations.

To manage this complexity, we believe organizations need a geostrategy, which we define as the integration of political risk assessment into risk management, strategy and operations. We view three steps as critical:

1. Scan the environment, establishing and maintaining the ability to identify, monitor, and assess political risk.

Questions for leaders:

- Do we use an outside provider of political risk intelligence?

- Are we tapping into the intelligence of our own company?

- Do we have a dynamic process around communication of risks?

- How do we stay informed around the important risks we face?

2. Focus on the impact on key performance indicators, mapping the political environment to the company footprint.

Questions for leaders:

- Who is responsible for a “whole firm” understanding of political risk impact?

- Are all functions touched by the risks being communicated?

- Do we have a dynamic communication network?

- Can we build a bespoke risk model? What new measurement efforts could be helpful?

3. Act to ensure they understand what risks to accept, what to mitigate and what can be influenced—developing a portfolio of robust political risk management instruments and building a growth-oriented geostrategy.

Questions for leaders:

- Are we too reactive to political risk?

- How can we work with local stakeholders to manage political risk?

- Do we understand the interests of local stakeholders?

- What strategies have worked for us in the past?

- What strategies have worked for others?

- Do we have the right skills on the board to help manage risks?

- Who is accountable for effective political risk management?

Achieving this higher level of capability requires collecting new data, adopting new tools and successfully implementing organizational change efforts to achieve their strategic cross-functional use.

To assess the experiences of firms advanced in this transition, we’re undertaking a broad-based benchmarking survey of political risk-management practices. We will conduct detailed interviews with firms at every level of capacity building, with high-performing firms oversampled. Insights from the survey and case studies will be shared with academics, managers and advisors at a summit on the topic of political risk management, as well as in an annual report.

It’s through understanding the political environment, its impact across the organization, and the strategic responses available that allows leaders to address the challenge, which is essential to driving sustained growth and protecting long-term value.

This article and associated report has been prepared in collaboration with Witold J. Henisz, PhD Professor of Management at The Wharton School, and Sven Behrendt, Senior Advisor to the Geostrategic Business Group.

Summary

Political risk is rising to new levels, driven by a series of long-term geopolitical undercurrents. This has a material impact across everything from sales to reputation. In this environment, comprehensive, strategic management of political risk can help to protect company value and increase growth opportunities.